What You Need to Know About Regional Steroid Injections and Alternatives

I see many patients eager to treat their painful joints with regional steroid injections. I urge them to weigh the risks and benefits carefully. Like all things in medicine, one size does not fit all, and alternatives to mainstream treatments are often safer and more effective in the long run.

Below, I’ll explain how regional steroid injections work, why doctors use them, why they’re not my first treatment choice, and what alternatives I recommend.

What Is a Regional Steroid Injection?

Corticosteroids, also called glucocorticoids, are injected directly into a specific affected area of the body to reduce local inflammation and relieve pain. Examples include shoulder and knee joints or the epidural space surrounding the nerves in the neck and back.

These injections’ effects are variable, ranging from no response to pain relief lasting from a few weeks to a few months.

Why Doctors Administer Steroid Injections

Administering a glucocorticoid regionally (as opposed to orally or injecting it into the bloodstream) exposes only a small part of the body to the drug and reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of system-wide side effects. However, even local side effects are possible.

The most common side effects that can occur at the injection site include:

- Hypopigmentation (loss of pigmentation)

- Joint infection because of reduced immune function

- Worsening of the adjacent bone’s integrity

- Atrophy (weakening of tendons, ligaments, and muscle in the region)

Can Local Steroid Injections Affect the Entire Body?

Yes, depending on the individual and the amount and type of glucocorticoid injected.

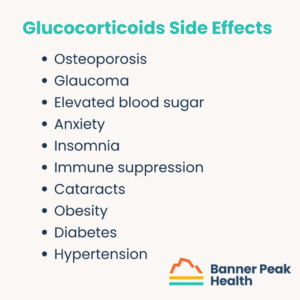

Glucocorticoids are a double-edged sword. They relieve pain, but they have a long list of detrimental side effects throughout the body. These include:

- Osteoporosis

- Glaucoma

- Elevated blood sugar

- Anxiety

- Insomnia

- Immune suppression

- Cataracts

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

These side effects could occur in the short term or long term, depending on the amount of drug injected and the exposure duration. The fewer glucocorticoids you expose your body to, the better.

Some demographics are at a higher risk of experiencing these side effects, including:

- Children — steroids can stunt growth

- People with osteoporosis — steroids can exacerbate the disease

- Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding — drugs can pass to the fetus

- Athletes — steroids injected near tendons or ligaments can increase the risk of rupture

- People with diabetes — steroids can cause sudden, extreme blood sugar spikes

- People with compromised immune systems — steroids can further compromise the immune response

- People prone to neuropsychiatric side effects (i.e., anxiety) — steroids can produce an acute anxiety response

There’s a movement afoot within the medical community to reformulate glucocorticoids so that they absorb more slowly. This would have two benefits:

- It keeps the drug in the joint longer, extending its effects (inflammation reduction and pain control).

- It’s a lower dosage, providing longer-lasting effects with less drug absorbed into the body.

Are There Alternatives to Steroid Injections?

Steroid injections are a Faustian bargain.

If you’re unfamiliar with the reference, Dr. Faustus is a character from a medieval German play. In the play, he trades his soul to the devil for unlimited knowledge.

Steroid injections may not be as malicious as the devil himself, but the trade for pain-free joints is risky.

If the risks aren’t worth it to you, you have a wide range of alternative solutions to choose from. I recommend the following:

- Topical NSAIDs (including diclofenac)

- Non-pharmacological remedies

- Resting the joint

- Physical therapy

- Massage

- Chiropractic care

- Acupuncture

Today’s Takeaways

I’m not a fan of steroid injections. They present a considerable amount of risk for the benefit they offer. Alternative treatments may provide benefits with far less risk.

Talk with your doctor, consider the risks, and explore all the options before choosing a safe route to healing.

How Long Does Blood Pressure Medicine Take to Work?

Patients with hypertension often ask, “How long does blood pressure medicine take to work?”

It depends. Most blood pressure medications take a few long weeks to reach their full effect — but there are steps you can take to lower your blood pressure in the meantime.

How High Blood Pressure Affects the Body

To understand how blood pressure medication works, you first need to understand what causes hypertension (high blood pressure).

Think of your blood vessels as an old-fashioned mechanical watch — one with dozens of interconnected gears and springs. When a single part malfunctions, the disruption spreads to other parts of the system, and the watch eventually stops working.

Repairing that one part triggers a chain reaction throughout the entire system, and the watch works better than it did before.

For a deeper exploration of blood pressure and its effect on the body, check out my blog post: A Physician’s Experience With High Blood Pressure.

How Long Does Blood Pressure Medicine Take to Work?

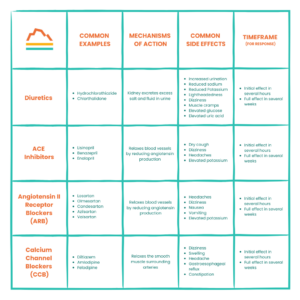

There are four common categories of blood pressure medication, but they all work within similar time frames. The initial effect occurs within hours but doesn’t reach its full effect for two to four weeks.

The following table describes the four common types of blood pressure medication, their mechanisms of action, and common side effects. The medication your doctor prescribes depends on your individual characteristics and risk factors:

How to Improve Your Medication’s Effectiveness

When your blood pressure is high, you want to lower it as quickly as possible. Making healthy lifestyle changes can boost your medication’s performance and reduce your blood pressure before your medication takes full effect.

Important: Lifestyle changes are not a replacement for professional help. If you have high blood pressure, you NEED to work with your doctor to lower it. Take your prescribed medication and follow your doctor’s advice.

While you’re doing that and waiting two to four weeks for your medication to reach its full effect, you can also (with your doctor’s approval!) make the following changes at home:

Reduce or Eliminate Unhealthy Foods and Substances

Some foods, drinks, and substances are notorious for elevating blood pressure. These include nicotine and alcohol.

Caffeine may be beneficial for some, but it can harm individuals with hypertension. While studies are still in progress, it’s best to reduce or eliminate your caffeine intake if your blood pressure is high.

Although sodium is necessary, excess salt is not. In the United States, virtually everything packaged, canned, frozen, processed, or served in a restaurant contains too much salt for someone with high blood pressure. Avoid excess salt by cooking fresh food at home or looking for foods with low sodium.

Adopt DASH

DASH (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) is a diet clinically demonstrated to lower blood pressure. The diet includes fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and low-fat dairy.

Exercise

Exercise is the closest thing we have to magic. Studies show that exercise, specifically strength training, for a minimum of 150 minutes per week can improve blood pressure independently of weight loss.

Weight Loss

While not everyone with high blood pressure needs to lose weight, many do. Losing just 5–10% of your body mass can profoundly impact your blood pressure if you’re overweight.

Losing weight when necessary can also improve other factors that contribute to high blood pressure, like sleep quality.

Sleep

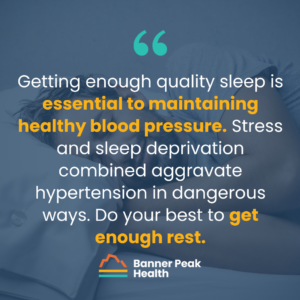

Getting enough quality sleep is essential to maintaining healthy blood pressure. Stress and sleep deprivation combined aggravate hypertension in dangerous ways. Do your best to get enough rest.

(If you aren’t getting enough sleep and need help figuring out why and how to improve your sleep quality, reach out today to discuss your options.)

Stress Reduction

We all know stress is the enemy of good health, but it’s especially insidious toward blood pressure.

Tackling your stress doesn’t have to be a chore. It can be as simple as reducing certain environmental noises with noise-canceling headphones or a white noise machine or meditating for a few minutes before hitting the hay. Spending time in nature has also been shown to reduce stress.

There are many ways to modify your environment and your lifestyle to reduce stress — you just need to find those that are most effective for you.

Today’s Takeaways

Now that we’ve answered the question, “How long does blood pressure medicine take to work?” and explored other ways of lowering blood pressure, the ball is in your court.

Follow your physician’s advice, take your medication as prescribed, and remember that there’s more to lowering blood pressure than taking a pill.

What Do Studies Show About the Relationship Between Stress and Memory?

Can you remember a stressful experience you had years ago with amazing clarity, but not what you had for dinner last night?

There’s a scientific reason!

Stress exposure directly impacts memory formation and retrieval. Sometimes, that’s helpful, and other times, not so much.

So, what do studies show about the relationship between stress and memory?

What Do Studies Show About the Relationship Between Stress and Memory?

Many studies explore how stress affects memory encoding and retrieval. The literature can appear contradictory.

To provide better clarity, I’ll break this topic down into three sections:

- How the timing of stress exposure affects memory formation and retrieval

- The body’s cortisol response

- Individual variation

How Does the Timing of Stress Exposure Affect Memory Formation and Retrieval?

We categorize stress into two groups: acute stress and chronic stress. Each triggers unique physiologic responses.

During acute stress (stress that occurs over the course of minutes or hours), memory is enhanced. According to the current theory, because your body’s cortisol levels spike during stress, brief spurts of cortisol enhance memory function.

This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. Consider what caused stress in cavemen (stumbling upon a lion’s den, for example) and why it was important to remember that information (so they could avoid that den in the future).

Chronic stress (ongoing stress over days, weeks, months, or longer) is different. When endured at high levels over time, cortisol becomes a neurotoxin. Although it’s our own hormone, it can damage vital parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, the region responsible for memory formation and processing.

To put things simply, acute stress helps both memory encoding and retrieval, and chronic stress hurts both memory encoding and retrieval.

How Does the Body’s Cortisol Response Influence Memory?

The memory formation and retrieval process is multi-layered, leaving many opportunities for individual variations.

The first layer is our hormonal stress response. This includes the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which determines how much cortisol the body secretes.

The second layer is how our brains function, including the size of different parts of the brain, which varies tremendously. These size variations determine how the hormonal stress response signal reaches the brain and how strong it is when it gets there.

The third and final layer is individual traits and personal history. For example, someone who’s been clinically diagnosed with anxiety or depression has a cortisol response that’s more highly attuned to their memory. Also, someone who has a history of trauma or PTSD has a more intense stress response, which also impacts their memory.

These three layers combined create the potential for tremendous variation in the relationship between stress and memory. This means that the same stress level can impact each person differently.

Physiological Presentations of Stress Depend on the Individual More Than the External Stressor

It’s easy to believe that a high-stress situation, such as a shootout with the police, would trigger a more severe biological response than a lower-stress situation, like watching a horror movie. However, that’s not always the case.

An individual’s stress response depends on the physiological variations I explored above. Take a man with PTSD, for instance. Watching “Saving Private Ryan” may trigger flashbacks and an elevated heart rate, but if his wife suffers a sudden heart attack beside him, he may remain calm, cool, and collected as he administers life-saving care and calls for help.

In other words, the factor that most influences the way stress presents is not the external trigger of the stress — it’s the person experiencing the stress.

This makes studying stress’s effects on memory challenging.

How to Mitigate Stress’s Negative Effects on Memory

Regardless of your individual variations, you can limit and improve stress’s effect on your memory by making healthy lifestyle choices.

I’ll sound like a broken record, but here are the best ways to help reduce stress and maintain or improve your memory formation and retrieval:

- Exercise regularly

- Consume a healthy diet

- Avoid unhealthy substances

- Get proper sleep

- Socialize

Here’s why these recommendations are vital:

Exercise

Studies demonstrate that exercise reduces stress and improves cognitive function.

“Neuroplasticity” refers to the brain’s ability to change through growth and reorganization. We used to think that young people’s brains would create new connections between neurons, and those connections would mature as they became young adults and remain the same for life.

Now, we’re realizing this isn’t the case.

Given the right conditions, we may be able to create new neural pathways throughout our lives. One condition is exercise, a method for improving hippocampal function. Since the hippocampus is intimately involved in memory function, there is evidence that exercise can help improve memory.

Diet

Diet choices, including consuming healthy fats, can also improve memory.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, flax seed, oil, and nuts, are an excellent source of healthy fats. Monounsaturated fats like olive, avocado, and various nut oils are also great.

Interestingly, fiber is also associated with improved memory function. We’ve come to understand that our gut microbiome affects almost every aspect of our health and that there’s a gut-brain connection. So, eating a bowl of oatmeal for breakfast might just help you ace that exam.

Unhealthy Substances

In case you needed another reason to avoid substances like nicotine and alcohol, studies demonstrate that they hurt memory formation and retrieval.

Caffeine, however, is not detrimental to memory. But using caffeine to compensate for poor sleep habits is like smacking a Band-Aid on top of a gaping wound.

Sleep

I’m always talking about the importance of sleep. Sleep is highly associated with memory function and stress reduction, which also improves memory.

So, try improving your sleep hygiene. It’ll improve your alertness more than that second pot of coffee.

Socialization

Decreased socialization and loneliness correlate with stress and an increased risk for dementia and impaired memory. Social interactions can help.

Therapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, can also reduce stress and improve memory function. So can mindfulness meditation.

Regarding Physical or Mental Illness

If you’ve been diagnosed with anxiety, depression, PTSD, or other mental or physical illnesses, talk with your doctor or seek other medical attention before making any changes to your routine, especially if you take medications.

Today’s Takeaways

We began this post by asking, “What do studies show about the relationship between stress and memory?” We’ve covered that and more:

- How stress can affect your memory

- How stress can affect your body

- How to address stress in a healthy way

If you need help managing your stress or have concerns about your memory function, reach out today. We’re here to help.

Can You Drink Coffee While Fasting? How to Do It the Right Way

My patients often ask me, “Can you drink coffee while fasting?”

My response is, “It depends. Why are you fasting?”

Fasting can mean many different things, so before I explore whether you can drink coffee while fasting, let’s define “fasting.”

Types of Fasting

Fasting means not eating for a period of time. This abstinence can also include drinking, depending on the type of fasting you’re partaking in.

For example, the Jewish faith defines fasting (such as for Yom Kippur) as going without food and drink (including water). When my Jewish patients schedule a fasting blood test, I need to remind them that they can drink water. It’s harder to draw blood from a dehydrated patient.

For medical purposes, such as blood draws, we at Banner Peak Health define fasting as abstaining from food for at least 12 hours, but drinking plenty of water is encouraged. This is similar to intermittent fasting, which many people practice as a weight loss method.

Drinking Coffee During Intermittent Fasting

When drinking coffee during an intermittent fast, the devil is in the details. In other words, it depends on what you add to your coffee.

Black coffee is fine since it only contains two to five calories per cup. However, once you add cream and sugar, the calories increase quickly:

- One teaspoon of sugar = 16 calories

- One pump of sweetened creamer = 10–20 calories

- Two teaspoons of whipped cream = 73 calories

- Two teaspoons of half & half = 40 calories

- Two tablespoons of non-dairy creamer = 20 calories

- Two tablespoons of oat milk = 15 calories

Benefits of Drinking Coffee During a Fast

It’s true — drinking coffee can be beneficial while fasting.

Coffee is a mild appetite suppressant, meaning it can fight hunger. It also increases alertness and combats caffeine-withdrawal headaches.

However, if a lack of caffeine causes headaches, you may want to consider why you need so much of it in the first place (e.g., are you getting enough sleep?).

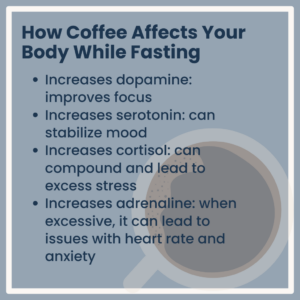

How Coffee Affects Your Body While Fasting

Coffee consumption impacts your hormone levels:

- Increases dopamine: improves focus

- Increases serotonin: can stabilize mood

- Increases cortisol: can compound and lead to excess stress

- Increases adrenaline: when excessive, it can lead to issues with heart rate and anxiety

Today’s Takeaways

The question “Can you drink coffee while fasting?” has no simple answer. It depends on why you’re fasting and what you like to put in your coffee.

Ultimately, if your fasting allows for drinking and your coffee doesn’t contain added cream, milk (dairy or plant), or sugar, enjoy it.

If you’re preparing for a blood draw, skip the Frappuccino for now.

Can Stress Cause Acid Reflux?

We’ve all heard the warning that stress causes ulcers. But is that true? Can stress cause acid reflux, ulcers, and an upset stomach?

It’s true! Your grandpa was right!

Today’s research demonstrates that people experiencing chronic stress are almost twice as likely to experience GERD symptoms. But how does it happen?

How Stress Impacts the Body

Stress has a huge physiological impact on the body.

In previous blog posts, I explained how stress affects heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood pressure. These indicators are functions of the autonomic nervous system, which comprises the sympathetic nervous system. This system mediates the fight-or-flight responses.

We also have a parasympathetic nervous system that mediates our rest and digest responses. To stay healthy, we need to keep these responses balanced. If these systems fall out of balance, disease is likely.

For example, in stressful situations, the sympathetic nervous system overwhelms the parasympathetic nervous system, impairing the digestive system. The result is that digestion slows down, and food backs up in the stomach and reverses direction.

Additionally, stress enhances our sensation of belching, bloating, and digestive discomfort due to hypersensitization of the nervous system. Stress increases the amount of acid produced in the stomach, which changes the content of the gut microbiome. This can cause or add to gastronomic symptoms.

This leads to a logical question: Why doesn’t all this excess acid digest our stomach lining?

While our stomach ordinarily contains a host of protective mechanisms, such as prostacyclin signaling, stress impairs their production. As a result, prolonged stress increases the risk of damage to the stomach lining, including ulcers and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

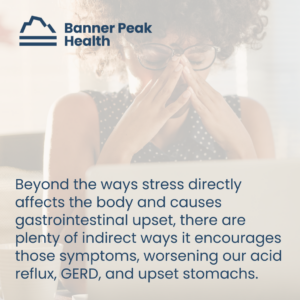

Other Ways Stress Can Cause Acid Reflux

Beyond the ways stress directly affects the body and causes gastrointestinal upset, there are plenty of indirect ways it encourages those symptoms, worsening our acid reflux, GERD, and upset stomachs.

Stress alters our behavior, and people under stress often make bad choices. They drink more alcohol, smoke more nicotine, and eat more “comfort food,” which usually contains more sugar and unhealthy fats. All these choices increase the risk of acid reflux, GERD, and stomach upset.

Are There Risk Factors for Acid Reflux?

Yes. Certain lifestyle choices increase your risk of acid reflux. These include:

- Alcohol consumption

- Nicotine use

Also, consider these other risk factors:

- Elevated body mass index (BMI), specifically intra-abdominal obesity

- Hiatal hernias

- Pregnancy

- Medications, including NSAIDs

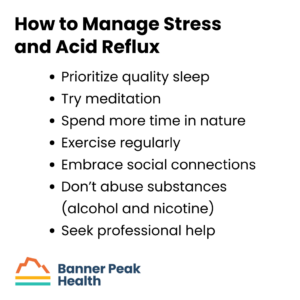

How to Manage Stress and Acid Reflux

Since stress has a direct biological impact on the digestive tract, it’s worth reducing it as much as possible. Focus on the most impacted aspects of your life, such as your sleep and exercise routines. Improving these is often the best way to reduce stress fast.

Sometimes, professional help is required, too. Stress’s impact often manifests as physical symptoms, such as stomach pain. If you can’t resolve these symptoms alone, don’t hesitate to seek help from a professional, whether that be your physician or a therapist.

Your mental health and your physical health operate hand in hand.

Today’s Takeaways

If you remember nothing else from this blog post, remember this:

You asked, “Can stress cause acid reflux?”

The answer is, “Yes. It does.”

The best thing you can do to improve your acid reflux is to manage your stress level. I’ve written about this extensively, but here are some quick tips:

- Prioritize quality sleep

- Try meditation (here’s a cheat sheet!)

- Spend more time in nature

- Exercise regularly

- Embrace social connections

- Don’t abuse substances (alcohol and nicotine)

- Seek professional help

As always, we’re here to help if you need us, and our blog is full of tips for improving your health and well-being.

How to Safely Find Your Blood Sugar Balance

Sugar can cause all sorts of bad health outcomes, from cavities to diabetes to cardiovascular issues. But when we say “sugar balance,” what exactly do we mean?

There are two definitions:

- ACEVA created a popular supplement called “Sugar Balance” and marketed it to diabetics. In 2021, ACEVA received a warning letter from the FDA to cease unsubstantiated medical claims, as Sugar Balance didn’t meet the FDA’s requirements for diabetes treatments. Supplements like this are dangerous and misleading.

- The “sugar balance” we’re discussing in this post is the balance of glucose in your blood. This is not a DIY topic. If you experience elevated blood sugar, consult your doctor — he or she will come up with an individualized treatment plan.

Let’s explore sugars (natural and added) and how to achieve a healthy sugar balance.

What’s the Difference Between Natural Sugars and “Added” Sugars?

Natural sugars are sugars naturally found in foods. They’re ingested in complete foods with protein, fiber, etc., digested slowly, and converted into glucose by your body.

Added sugars are a part of food processing and are often high-fructose sugars derived from corn syrup. They’re added for taste, not nutrition.

Your body absorbs these sugars rapidly, leading to “sugar rise, sugar crash” cycles. The rapid rise, especially because of fructose, is associated with excess caloric deposition in the liver as fat, which can cause non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Since these calories aren’t associated with other nutrition, we call them “empty calories.”

Where Does Sugar “Hide”?

Sometimes, sugar hides in plain sight. Even foods we think of as “healthy” hide empty calories.

There are four calories in every gram of added sugar. Consider the following sugar amounts:

- Flavored yogurt: Up to 32 g in 6 oz

- Instant oatmeal: 10 to 15 g per packet

- Peanut or almond butter: 6 g per two tablespoons

- Granola bar: 8 to 10 g

- Canned fruit: Up to 26 g per cup

- Protein bar: Up to 22 g

Read those nutrition labels and pay attention to what you eat.

How to Achieve a Healthy Sugar Balance

How can you achieve a healthy blood sugar balance? Can (and should) you do more than just cut sweets from your diet?

A healthy fasting blood glucose range is between 70 mg/dl and 99 mg/dl. You can keep your blood glucose in this range by:

These methods will help whether you currently have health complications or not. However, if you’re diabetic or at risk for developing diabetes, continuous glucose monitoring can also be extremely beneficial. Discuss your options with your doctor before starting a new treatment plan.

Sugar Is Not Your Friend

Consistently elevated serum glucose is associated with a host of poor health outcomes, including:

- Myocardial infarctions

- Cancer

- Stroke

- Pre-diabetes and diabetes

- Diabetic neuropathy

- Blindness

- Kidney disease

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Glaucoma

And more. Consuming excess sugar can shorten your lifespan and healthspan, especially if you already have health conditions like diabetes that require careful monitoring. Avoid these consequences by avoiding added sugar and maintaining a healthy sugar balance.

If you’d like guidance from a trusted expert, reach out to Banner Peak Health. Our team of physicians is excited to help you live your longest, healthiest life.

Night Sweats: Understanding the Causes and How to Stay Cool

Do you often wake up in the middle of the night sweating, throwing the blankets off, turning up your fan, unable to find relief? Do you get up in the morning exhausted, asking, “Why do I get so hot when I sleep?”

You’re not alone.

Fourteen percent of American adults say they always feel too hot when they sleep, and another 43% say they “occasionally” do. What causes all this overheating? What can you do about it?

How Your Body Regulates Its Temperature During Sleep

Our circadian rhythm dictates the timing of almost all our biological processes, including sleep, digestion, and temperature regulation.

If our circadian rhythm deviates from its norm, we may feel too hot or cold while we sleep.

Common Contributing Factors

Several factors can throw our circadian rhythm out of whack.

We (humans) are inefficient from a metabolic perspective. We’re analogous to an incandescent lightbulb — about 75% of our energy intake from ingested calories goes toward heat generation rather than motion or growth.

Thus, anything that increases our metabolism generates excess heat. Common factors include:

- Evening exercise (within four hours of bedtime), which jump-starts our metabolism

- Some medications

- Infections with low-grade fevers

- Certain cancers

- Hormonal conditions, including:

- Menopause, which reduces estrogen levels

- The luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, which can increase the body’s temperature by around 0.3°F (0.7℃)

- Pregnancy, which increases progesterone levels

- Hyperthyroidism

Although some factors are unavoidable, you can strive to increase your sleep comfort. We’ll explore some methods for cooling down at night. However, if your symptoms persist, you should contact your doctor for an exploration of the underlying cause.

Creating the Optimal Sleeping Environment

Our circadian rhythm includes a drop in core temperature of up to 1.8°F over the course of the night. Excess heat can interfere with this process and hamper our sleep. Follow these suggestions to stay more comfortable at night:

- Set your thermostat between 60°F and 67°F

- Use light bedding, such as cotton, linen, or bamboo — all materials with good ventilation

- Wear lightweight pajamas

- Reduce your stress:

- Exercise earlier in the day

- Spend time outside

- Meditate

- Avoid caffeine and alcohol

- Regularly connect with friends and family

Today’s Takeaways

If you’re struggling to answer the question, “Why do I get so hot when I sleep?” practice the tips in this post and see if you can find relief.

Here’s a quick summary:

Determine why you’re overheating:

- Exercising too late?

- Side effect of a medication?

- Do you have an infection or a fever?

- Do you have a hormonal imbalance?

Try these tips to find relief:

- Set your thermostat between 60℉ and 67℉

- Use lightweight bedding, such as cotton, linen, or bamboo

- Wear lightweight pajamas

- Reduce your stress:

- Exercise earlier in the day

- Spend time outside

- Meditate

- Avoid caffeine and alcohol

- Regularly connect with friends and family

If none of those help, ask your physician about other solutions.

Remember, healthy sleep is crucial to overall wellness. Don’t underestimate its importance, and don’t procrastinate getting help.

We at Banner Peak Health are happy to help optimize your sleep. Contact us today to discuss solutions.

Why Is My VO2 Max Going Down? (And How to Increase It)

More people are discovering the importance of VO2 max and have begun using wearables like Garmin, Oura Ring, and Apple Watch to monitor it. But what happens if your VO2 max suddenly drops?

In this blog post, I’ll explain VO2 max and its importance. I’ll also answer the questions, “Why is my VO2 max going down?” and “How can I increase it?”

What Is VO2 Max and Why Is It Important?

VO2 max is the maximum rate of oxygen your body can use during exercise. It includes a measurement of oxygen in millimeters (volume) per minute (rate) and per kilogram (across body size).

VO2 max assesses the health of your entire cardiovascular system, including heart, lung, and blood vessel function. It even evaluates muscle cells down to their mitochondria. It’s an extremely accurate predictor of all-cause mortality.

Why Is My VO2 Max Going Down?

A decline in VO2 max can alarm people who exercise regularly. Here are a few reasons you may notice a reduction in your VO2 max:

- Anyone can have a bad day. Various reasons include a lack of sleep, over-exercising, illness, or stress.

- A medium-term decline over weeks may occur due to weight gain or insulin resistance (more on this in a bit).

- Age-related declines.

- Anemia.

How to Improve Your VO2 Max

Improving your VO2 max comes back to how you measure it.

The gold standard for measuring your VO2 max is a stress test, which involves running on a treadmill or riding an exercise bike to complete exhaustion while having your breath monitored for changes in oxygen concentration.

Many assume that to improve your VO2 max, you need to put yourself under intense mental and physical stress to be valuable.

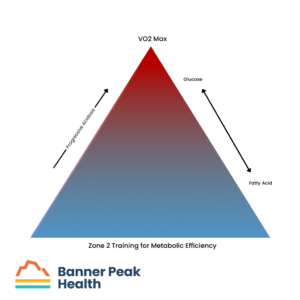

Evidence does support that HIIT (high-intensity interval training) can improve your VO2 max; however, it’s not the only way. You should also participate in Zone 2 training.

How can large amounts of time spent plodding along at a conversational pace help you maximize your ability to go so fast you can barely breathe? The answer to this paradox involves understanding the metabolic efficacy of Zone 2.

For exercise, our muscles use two fuels as energy: fatty acids and glucose. At slower speeds, we metabolize fatty acids and can go all day. Fatty acids are “clean fuel.”

At faster speeds, we metabolize progressively more glucose. The process creates progressively more acidosis and causes symptoms including increased heart rate, shortness of breath, and burning muscles. Our struggle with acidosis is why we can’t maintain faster paces as long as slower ones.

Therefore, the longer you can go while being fueled by fatty acids, the greater the speed you can reach before your body switches fuel sources, which causes you to feel the effects of acidosis.

What About Genetics?

What About Genetics?

Although we all start with different genetic propensities for VO2 max, we’re all capable of improving it with a concerted effort.

No matter our age or genetic background, there is room for improvement.

Don’t Panic

As more people learn about VO2 max’s importance, it’s crucial to understand that current wearables aren’t advanced enough to accurately measure VO2 max. I track mine with both a Garmin device on my bike and the gold standard. The Garmin device varies with up to a 25% error.

So, if you look at your wearable and see a result that makes you ask, “Why is my VO2 max going down?” don’t panic. Periodically check your wearable against the gold standard for a correlation.

If you’re a Banner Peak Health member, we’re happy to help. Schedule an appointment today.

What Supplements Lower Cortisol?

What supplements lower cortisol? Unfortunately, the answer may be none.

Many short-term studies of supplements show a transient reduction in cortisol. However, because these studies aren’t long-term, they don’t address years-long health issues.

Also, supplement manufacturing is unregulated. There’s no guarantee that the substance reviewed in those studies is the same as what’s in the bottle you purchase.

Taking a pill means you’ve chosen a short-term cost over a long-term investment. It may yield poor results, and you’ll likely be disappointed.

In this blog post, I discuss cortisol, what supplements lower cortisol (or don’t), and how you can successfully regulate your cortisol naturally.

What Is Cortisol?

Cortisol is a stress hormone your adrenal glands release when they receive a signal from your hypothalamus. This process is part of your fight-or-flight response.

There are times when your body rests, digests, or reproduces. Other times, when you enter “fight-or-flight” mode, your body is triggered to release adrenaline (also called epinephrine) and cortisol.

These chemicals pulse through the bloodstream, increasing blood glucose and heart rate as they prepare our bodies for action. This hormonal activity can last from a few minutes to several hours.

Among these chemicals is a neurotransmitter called norepinephrine, which also mobilizes the body for physical activity. Cortisol is released from a different part of the adrenal gland than norepinephrine and responds much slower — it can last many hours.

Think of epinephrine and norepinephrine like soldiers stationed at your body’s front lines, ready to fight at a moment’s notice. By contrast, cortisol is on a slow-moving train. As the train brings cortisol to the front lines, it’s unable to take resources to other parts of the body.

When our bodies sustain cortisol over long periods (such as in the case of chronic stress), it hurts almost every other bodily system. From digestion to immune function to reproductive issues, the effects of sustained cortisol are myriad and often dangerous.

What Supplements Lower Cortisol?

Like you, I’ve seen supplements online that allegedly lower cortisol, such as:

I’m skeptical of these supplements. The more treatments exist to address one health issue, the less likely those treatments are to be effective. If one of them worked, we wouldn’t need alternative options. We’d all use that one treatment.

I’ve also looked into the existing research, and I’m not impressed. As I mentioned earlier, they’re short-term and minimal at best. The best example I could find was a meta-analysis (a review of multiple studies) of ashwagandha. Unfortunately, only seven studies met the criteria for review, and of those seven, only five showed reduced cortisol. There were side effects and uncertain formulation.

The literature is lacking. Sure, supplement manufacturers can say “studies show,” but those studies aren’t high-quality.

The Allure of a Magic Pill

I understand the appeal of a magic pill, and I wish I could prescribe one to my patients. The compulsion to find an easy fix is human nature.

But we’re adults. We’ve lived enough life to realize that’s not how it works. You don’t get anything of value for free. If you want something worth having — long-term health, for example — you’ve got to work for it.

Stress-Beating Strategies

So, what supplements lower cortisol? Right now, none. Thankfully, there are other ways to lower cortisol.

Stress reduction is the best way to lower your cortisol. That’s much easier said than done, which is why we work with our members to develop personalized stress-management strategies. These strategies may include:

- Limiting alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine consumption

- Building community

- Improving sleep hygiene

- Exercising regularly

- Having a purpose

Those are the foundations of a healthy life. But you can’t manage what you don’t measure, so we also recommend tools that monitor your HRV (heart rate variability). Knowing your HRV can help you manage your stress.

As always, we’re here to help you reach peak health. Contact us any time.

How to Get More REM Sleep: Proven Strategies for Quality Rest

Adequate sleep maintains optimal health in both body and mind.

Sleep helps your body:

Sleep helps your body:

- Maintain peak physical performance

- Maintain immune function

- Repair injuries

- Control weight

Sleep helps your mind:

Let’s explore REM, why it’s important, and how to get more REM sleep.

What Is REM Sleep and Why Is It Important?

Your sleep architecture is divided into 90-minute cycles. Each cycle includes stages of lighter sleep, deeper sleep, brief periods of wakefulness, and REM sleep.

REM stands for “rapid eye movement” because, during this stage of sleep, our eyes move rapidly under our eyelids. Brain waves during this stage are the same as when we’re awake, but we cannot use our muscles, so we can’t move. During this sleep stage, we dream, and the inability to move our muscles prevents us from acting out our dreams.

During this crucial stage, our brains consolidate our memories, and we attach emotional impact to them.

How to Get More REM Sleep With Better Sleep Habits

The sleep cycles that repeat every night are influenced by other bodily functions (some related to hormone release) that occur earlier in the day. How these cycles are timed determines how well we achieve REM sleep that night.

You can improve and increase your REM sleep with some simple changes in your sleep habits.

Many people have heard advice about light exposure, including avoiding blue light before bed, but there’s much more to “light theory” and circadian rhythms. Research demonstrates that the best light exposure to optimize your circadian rhythm is “first morning light” or “dawn light.” It’s one of the most potent signals we have to set (or reset) our circadian rhythms. Sleeping well at night begins with good light exposure first thing in the morning.

I’ve also discussed the TUO Life Bulb, which you can use at home to obtain good morning light exposure.

Another crucial step is to avoid the alarm clock whenever possible. Waking up to an alarm clock isn’t a pleasant way to start your day. Also, the last 90-minute sleep cycle of the night contains the most REM sleep. An alarm clock interrupts your natural sleep cycle at possibly the worst time — at the end, robbing you of valuable REM sleep.

Alarm clocks are REM killers, but they aren’t the only ones. Anything that hurts your sleep hurts your REM sleep. For example, obstructive sleep apnea is one of the biggest sleep impairers we help our members tackle, but we have a not-so-secret weapon.

How Banner Peak Health Can Help You Get More REM Sleep

We’re excited to work with a new sleep image device that allows you to screen for obstructive sleep apnea by wearing a small rubber ring that transmits a signal to your smartphone.

Through advanced technology and other lifestyle changes, we enjoy helping our members figure out how to get more REM sleep and feel refreshed daily.

How to Get More REM Sleep by Changing Lifestyle Factors

Any factor that enhances your sleep quality also enhances your REM sleep.

My best advice regarding how to get more REM sleep is:

- Be cognizant of the chemicals you ingest (e.g., alcohol, caffeine) and their effect on your body. Some patients are more sensitive than others.

- Use stress-reduction techniques like meditation.

- Follow the suggestions in this blog post.

- Get adequate exercise.

If you need more help or have additional questions, reach out. We’re happy to talk.

Sleep is medicine. It affects every aspect of your health. Getting adequate sleep is one of the best things you can do for your body. Don’t underestimate its value.