Asking, “What’s my blood pressure?” is like asking, “What’s the weather like in Omaha, Nebraska?”

The weather in Omaha can change from minute to minute and depends on many variables, including the season and time of day. Your blood pressure is the same and can vary depending on a wide array of variables including emotions, activity, sleep, pain, and beverages such as coffee and alcohol products.

Blood pressure is the pressure exerted by circulating blood against the blood vessel walls. When the heart contracts, blood pressure peaks. As the heart relaxes, blood flows into the heart chambers, reducing blood pressure.

We describe blood pressure using a larger number over a smaller number. The larger number is the peak blood pressure during the squeeze, or the systolic phase. The smaller number is the low point of pressure as the heart relaxes, or the diastolic phase.

Our current definition of “normal” blood pressure is less than 120 over 80. “High blood pressure,” or hypertension, occurs in stages and puts you at a greater risk for a constellation of bad health outcomes, including:

- Kidney failure

- Stroke

- Heart failure

- Heart attack

- Heart arrhythmia

Therefore, it’s vital to accurately measure blood pressure and treat it in order to help prevent these clinical outcomes.

It’s also essential to understand that the journey to these bad outcomes begins with mildly elevated pressure, which leads to stiffer blood vessels that require higher blood pressure to move the blood, which causes the vessels to stiffen further, and so on. The progressive loss of elasticity becomes a feed-forward loop. The earlier we can interrupt the pattern of elevated blood pressure, the more we can reduce the risk of bad outcomes.

The Challenge of Measuring Accurately

Returning to our weather metaphor, just as the weather changes constantly, so does your blood pressure. Throughout the day, your blood pressure goes through peaks and valleys, resembling a seismogram during an earthquake.

The variability results from circumstances such as your activity level, food and drink choices (caffeine and alcohol can affect blood pressure), stress level, and technicalities regarding how you measure your blood pressure.

To record “accurate” blood pressure, a person:

- Should be at rest for at least five minutes

- Must abstain from caffeine, alcohol, and cold medicines

- Must sit upright in a chair that supports the torso, legs uncrossed, with their feet flat on the floor

- Must not be in pain or dizzy

- Must keep the blood pressure cuff at the level of their heart

Meeting the Challenge

The following common scenarios can lead to erroneous blood pressure readings:

- Sitting in traffic on the way to the doctor (high stress increases blood pressure)

- Experiencing a symptom (e.g., a headache)

- Placing the blood pressure cuff lower than the heart

- Drinking alcohol the night before

- Drinking coffee the morning of

- Taking an NSAID the morning of (increases blood pressure)

SPRINT Study

When I read medical literature, I ask myself whether the intervention described in the study applies to what occurs in my clinic. Sometimes, it’s not even close.

Take the SPRINT study, which demonstrated that patients with elevated blood pressure whose treatment resulted in a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 had one-third the risk of stroke, heart attack, and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events compared to those who were treated to the target of 140.

This study created the rationale for our current blood pressure target guidelines. However, researchers involved in the study measured blood pressure very differently than the standard practice.

Study participants would enter a room and sit quietly for five minutes before a machine automatically took their blood pressure. They’d continue to sit quietly as the machine took their blood pressure at five-minute intervals for 15 minutes. The three measurements were averaged.

This scenario is nothing like a the usual clinical context — no nurses, no doctors entering or leaving the room, etc. It’s exceptionally difficult to replicate in a real-world application. The study’s results achieved lower blood pressure, but only in specific circumstances.

Be an Active Participant

So, how can we get more accurate blood pressure readings?

First, we must understand that blood pressure readings taken in a clinical environment, such as in a doctor’s office during a standard appointment, are often inaccurate.

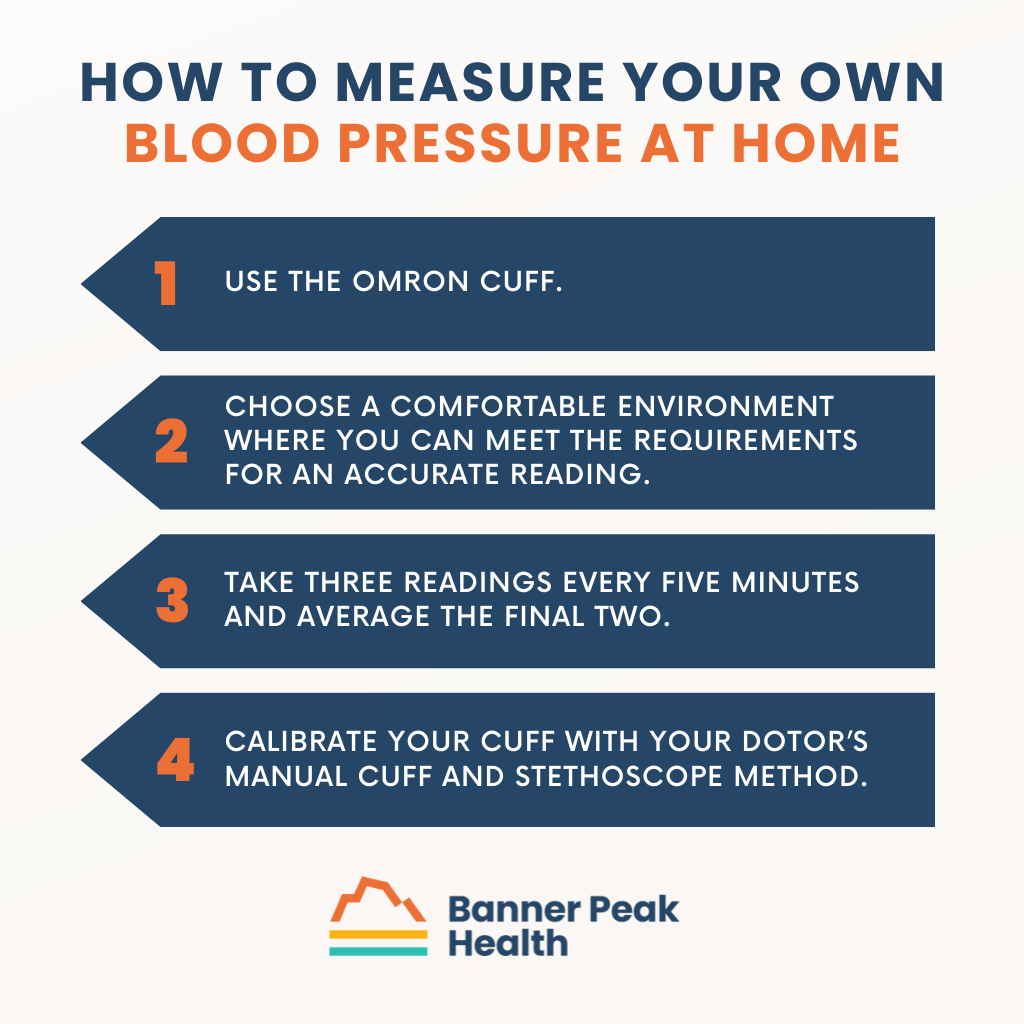

Patients need to measure their blood pressure on their own at home. Follow these tips:

- Use a high quality machine such as the OMRON cuff.

- Choose an environment where you can rest comfortably and meet the other requirements for an accurate reading (as listed above).

- Take three readings every five minutes and average the final two.

- Take your cuff to your doctor’s office to calibrate it with their manual cuff and stethoscope method.

Any time you have your blood pressure taken, be an active participant. Point out the conditions that may affect your reading and take steps to ensure as much accuracy as possible.

Barry Rotman, MD

For over 30 years in medicine, Dr. Rotman has dedicated himself to excellence. With patients’ health as his top priority, he opened his own concierge medical practice in 2007 to practice medicine in a way that lets him truly serve their best interests.