Rise and Shine: How to Wake Yourself Up

My patients often tell me, “I’m having trouble waking up in the morning.” They want help feeling less fatigued and more energized.

As adults, we’ve experienced tens of thousands of sleep-wake cycles, yet we haven’t mastered it. If you’ve read anything I’ve written, you know sleep hygiene is a passion of mine. It’s vital to our health, and far too few of us enjoy enough good nights of sleep. I want to change that.

Today, I’m discussing how to wake yourself up without lingering fatigue.

The Two Determinants of the Sleep-Wake Cycle

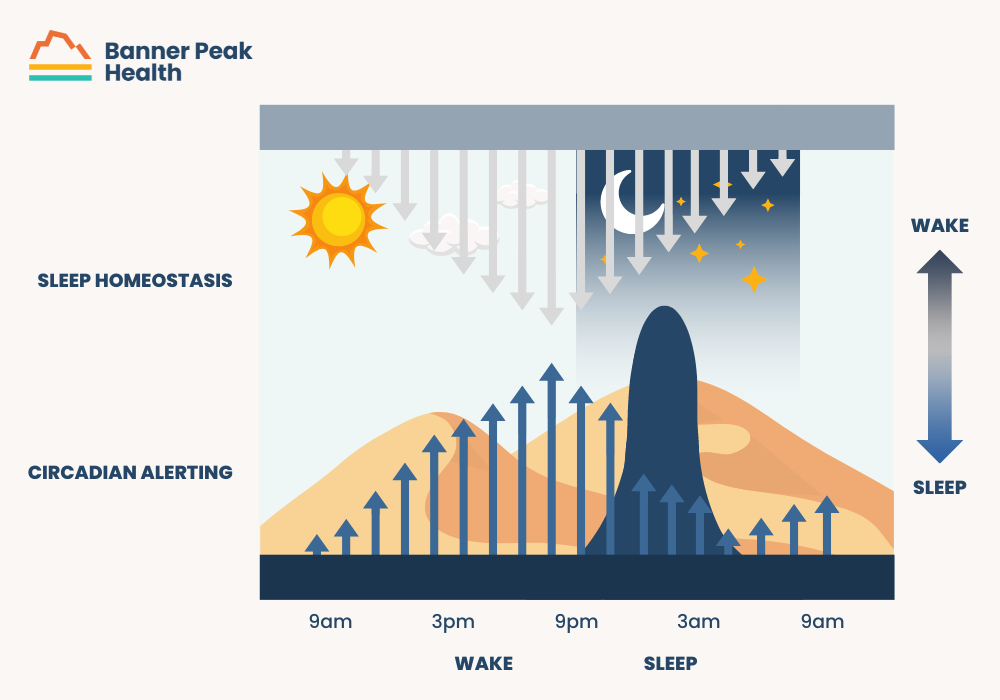

Two concepts work together to create our sleep-wake cycle: sleep homeostasis and circadian rhythm.

Sleep Homeostasis

Analogous to sand falling through an hourglass, the sand is the chemical adenosine. From the moment we wake up, adenosine begins to pile up. The more adenosine we have, the more it suppresses our body’s ability to remain awake.

Fun fact: Caffeine blocks adenosine receptors in the brain. This means caffeine masks the signal of fatigue from our brain that the adenosine triggers. The hourglass is still filling up — our brain just can’t “see” it until the caffeine wears off.

Circadian Rhythm

I’ve written quite a bit about the circadian rhythm.

It’s controlled by our suprachiasmatic nucleus, our internal, intrinsic, 24-hour biochemical clock that synchronizes with the outside world. Neurons connect our retinas to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and our hormones tell us to be awake during the day and asleep at night.

For example, when the sun sets, less light reaches the eye. This reduction in light causes the suprachiasmatic nucleus to signal more melatonin, which creates sleepiness and causes the body to fall asleep.

Conversely, even through closed eyelids at sunrise, we perceive more light, suppressing melatonin and reversing hormonal changes, such as increasing cortisol and body temperature. That’s how we wake up.

These systems work in tandem.

How to Wake Yourself Up Better

Now that you understand how you fall asleep and wake up, it’s time to learn how to wake yourself up better to feel refreshed.

You must adhere to your natural sleep cycle. But how can you do that, especially in today’s busy world?

Get Enough Sleep

Get Enough Sleep

Returning to our hourglass analogy, start with an empty hourglass. Your hourglass fills itself with fatigue throughout the day and empties itself each night, so ensure that you empty that hourglass completely every night. Do that by getting enough sleep to reset your homeostasis.

Studies show that the average adult needs between seven and nine hours of sleep per night. Children and teens need more sleep than adults in order to remain healthy.

Follow Your Circadian Rhythm

Synchronize your circadian rhythm and hormones rather than fight against them. There are two chronotypes:

- Night owls: People whose circadian rhythm is longer than 24 hours and whose energy peaks later in the day.

- Morning sparrows: People whose circadian rhythm is shorter than 24 hours and whose energy peaks early in the day.

By identifying your chronotype, you can live in sync with your hormones and enjoy the benefits, such as better focus, sleep, and energy.

Use Light to Sync Your Internal Clock

First morning light cues our internal clocks to wake up and start the day. It has to do with the spectrum of morning light.

We can use this knowledge to our advantage when traveling to reduce jet lag or reset our circadian rhythms anytime we need. Simply avoid wearing sunglasses first thing in the morning and enjoy the morning light.

To bring the same spectrum indoors, try TUO light bulbs, which use the same light as morning sunlight. I highly recommend them.

Avoid Chemical Hangovers

We’re all familiar with alcoholic hangovers, but other chemicals can produce unpleasant effects the morning after, too.

Various OTC medications cause drowsiness as a side effect, including Tylenol PM and Advil PM. These medications contain diphenhydramine, which stays in the body longer than the duration of your sleep and can lead to a strong chemical hangover. Be cognizant of these side effects and talk to your doctor if they become worrisome.

Many prescription medicines have similar side effects, so review potential side effect information with your doctor or pharmacist.

Beware the Alarm Clock

Our sleep cycles through light sleep, deep sleep, and REM sleep about every 90 minutes. We call this sleep architecture. If you wake up during deep sleep or REM sleep because your alarm clock goes off, that’s an unnatural time in your sleep cycle, so you’re more likely to wake up groggy and exhausted.

If possible, wake up naturally rather than with an alarm clock.

Today’s Takeaways

You asked how to wake yourself up with less fatigue, and now you have five tactics to improve your sleep and boost your energy in the morning, no coffee required. They’re easier said than done, but nothing worth doing is easy.

Improving your health, quality of life, and energy are worth the effort. If you have questions, reach out to us. We’re here to help.

What Is the Normal Blood Pressure? Well, It’s Complicated…

We all want normal blood pressure. But what is the normal blood pressure for you? It’s a more complicated question than it seems.

Blood pressure is crucial to overall health, but how do we learn what our normal is, and how do we monitor it once we do?

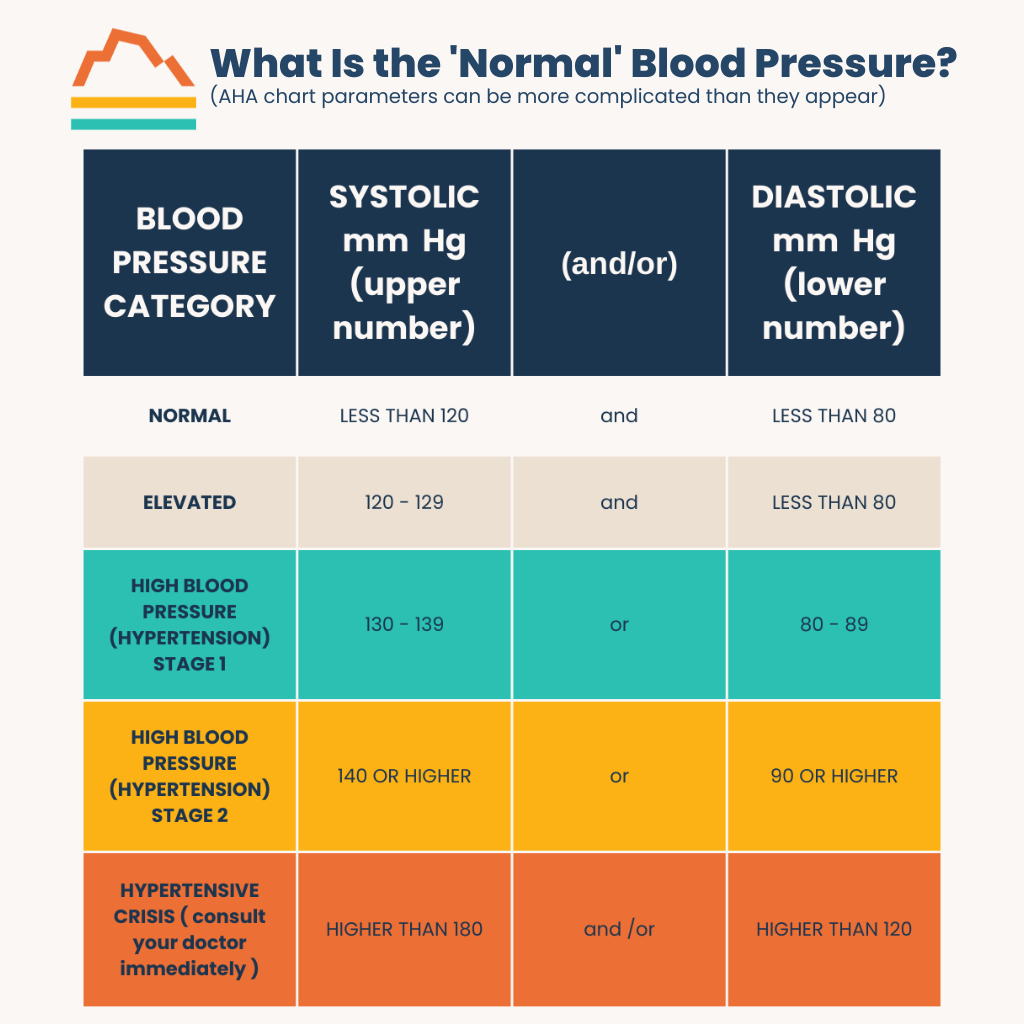

What Is the “Normal” Blood Pressure?

The chart below reflects the American Heart Association’s parameters for “normal blood pressure.” However, those parameters are more complicated than they appear.

The numbers corresponding to “normal” in the chart are the blood pressure goals for healthy adults, not the results for the average American adult. The average blood pressure isn’t desirable from a health perspective because nearly half of American adults are hypertensive.

The “normal blood pressure” target has also changed significantly in the nearly four decades I’ve been in medicine. “Normal” blood pressure was defined as under 160 systolic in the 1980s, according to the SHEP study. The American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology updated those guidelines to 140 systolic in 2014.

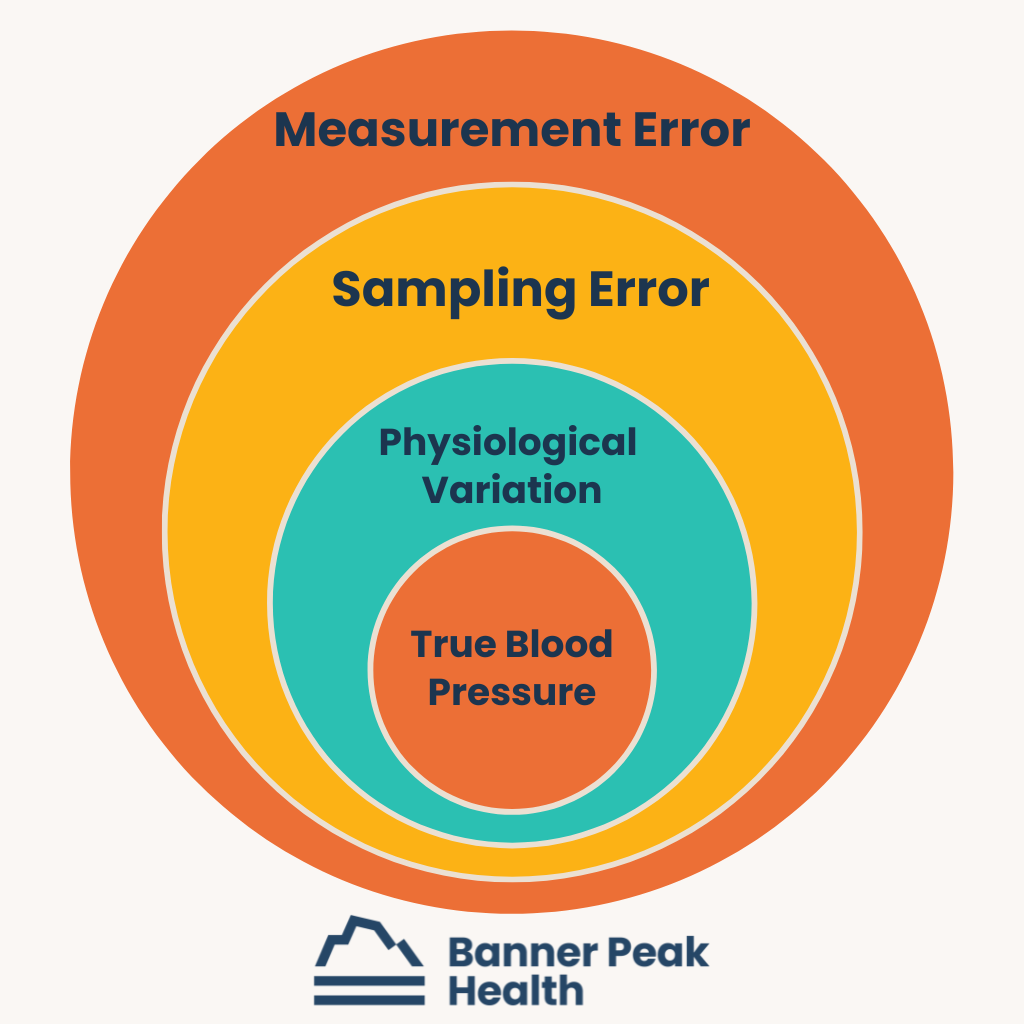

How Your Blood Pressure Measurement Changes

Medical guidelines recommend that adult blood pressure be lower than 120 or over 70, based on the SPRINT study. But even this recommendation isn’t straightforward. Many factors influence your measured blood pressure from minute to minute, and they compound like Russian nesting dolls.

For example, the study that determined the latest “normal blood pressure” did so by averaging the blood pressures of healthy adults taken every five minutes as the participants were calm and at rest without a doctor’s presence. Compare those conditions with the conditions under which you typically have your blood pressure taken — immediately after sitting down in an anxiety-inducing doctor’s office — and you can see why your blood pressure may not measure up to the standard.

Physiological Variations

Blood pressure changes constantly, like the weather, because of physiological variations, including body position, exercise, stress level, etc. Measuring it accurately requires a standard of conditions seldom met in daily life.

Sampling Errors

Blood pressure measurements also vary because of sampling errors. For instance, taking your blood pressure immediately after rushing into your doctor’s office after facing frustrating traffic is a bad idea. The measurement will probably be high and inaccurate.

Equipment and Technique Errors

Finally, errors stem from misused equipment and misapplied technique.

Common mistakes include using wrist cuffs. These measure blood pressure at the radial artery, which differs significantly from the brachial artery (the artery in your upper arm). Comparing the numbers from a wrist cuff to those in a chart meant for an arm cuff yields inaccurate results.

Another common mistake is positioning the arm lower than the heart. This position creates additional pressure in the artery and throws the measurement off. Having the wrong-sized cuff also leads to inaccurate measurements.

Getting an Accurate Blood Pressure Reading

How can you get an accurate blood pressure measurement? Be an educated consumer.

The SPRINT study taught us that the most accurate blood pressure measurement is taken at home, not at the doctor’s office. We need to be calm and comfortable.

That said, the simple task of determining blood pressure is not a simple task.

Understanding your blood pressure as an average or trend rather than a single measurement or number is important. Be familiar with your body and have conversations with your doctor about what is the normal blood pressure for you. Staying informed and engaged is the best way to stay healthy.

Can a Metabolic Panel Detect Cancer?

An estimated two million new cancers will be diagnosed in the U.S. this year, and over 611,000 people will die from cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute. Unfortunately, cancer will impact so many lives.

Scientists and doctors constantly search for better ways to detect and treat cancer. Metabolic blood panels are one tool we use, but can a metabolic panel detect cancer?

What Is a Metabolic Panel?

A metabolic panel is a blood test that provides a high-level view of the body’s major organ systems. It’s a dashboard that shows how the liver, kidneys, and blood sugar are doing. It also gives insights into white and red blood cell counts.

The term pathophysiology means “how does it come to be.” Once you understand the pathophysiology of cancer, you’ll better understand metabolic panels’ role in the care of cancer patients.

What Is Cancer?

Cells rewrite their blueprint each time they grow and divide. This process can cause errors, and with each error, the cell’s function degrades until, finally, it doesn’t work properly. This is when the cell becomes cancerous.

Cancer is a cell that’s so abnormal that it’s become dangerous. It has unregulated growth, risking local invasion into adjacent tissue. For example, a cancer that starts in the pancreas can spread into adjacent areas of the digestive system. Also, cancer cells can also spread metastatically, beyond the cell’s original location. This can occur with breast cancer, where the cancer cells spread to the lungs, bones, and brain.

Can a Metabolic Panel Detect Cancer?

Returning to the question, “Can a metabolic panel detect cancer?” the answer is yes, but it is not an effective screening tool. Unfortunately, by the time there’s enough cancer in the bone marrow, liver, or kidney to be detected by a metabolic panel, the cancer is often in stage four — metastatic cancer — and it’s too late to treat it effectively.

We need a better method of detection and screening to detect cancer earlier and treat it more effectively.

Are Metabolic Panels Useful for Monitoring Cancer?

Metabolic panels are excellent monitoring tools. They allow us to track known cancer’s effects on the body.

For example, the more cancer cells lodge in the liver, the more they disturb the functioning of the liver. We can monitor the health of the liver using metabolic panels. These insights help us better understand the cancer’s impact on the body.

Using Metabolic Panels in Cancer Care

Perhaps the best use of metabolic panels in cancer care is monitoring the effects of potentially dangerous cancer treatments on patients.

We can use metabolic panels to monitor potential drug toxicity associated with cancer treatment. Cancer treatments can affect the bone marrow, liver, and kidneys, so we can use metabolic panels to monitor those areas closely.

What Early Cancer Detection Tool Is Most Effective?

The best early cancer detection tool we have (for adults over age 50) is the Galleri test. Galleri is a powerful cancer screening test developed by GRAIL.

With Galleri, we can screen for a DNA “fingerprint” common to over 50 types of cancer. The test uses a simple blood test to find the DNA signal. If the test finds the signal, your physician will discuss the next steps to diagnose a potential cancer.

If you think the Galleri test might be appropriate for you or you have more questions about it, contact us. We’re happy to answer any questions you have.

Today’s Takeaways

We’ve answered the question, “Can a metabolic panel detect cancer?” Technically, it can. However, it’s a poor screening tool that detects cancer too late for effective treatment. The Galleri test is a more effective screening tool that catches the disease early enough to save lives.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of care. Stay up-to-date on your screenings, and let your doctor know if you have any questions about your health.

Fall Vaccine Update 2024

Fall is on its way. It’s time to attend tailgate parties, break out your wool sweaters... and receive your vaccine recommendations from Banner Peak Health.

We’ll update our recommendations for the three vaccines we discussed last year: respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza, and COVID.

Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Last year, we were tentative about the RSV vaccines: Abrysvo by Pfizer and Arexvy by GSK. The initial randomized controlled trials showed a reduction in symptom burden but failed to demonstrate a reduction in hospitalizations and deaths.

We were also concerned about the higher rates of two potentially fatal autoimmune central nervous system diseases: Guillain-Barré syndrome and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis.

These very rare complications occurred in 1 out of 7,500–15,000 study participants. This rate is much higher than usual than in other vaccines, such as influenza and Shingrix (shingles).

We didn’t support drug companies’ recommendation that “everyone over sixty years old” receive the vaccine. We advised that only high-risk individuals over sixty years old and their close contacts receive the vaccine as we wait for more data.

A year later, we still don’t have randomized controlled trials or epidemiological studies documenting a reduction in death or hospitalization from RSV. It may be too soon for those studies to be completed.

Regarding the risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported estimated rates for over 10 million people who received the vaccine from August 4, 2023, to March 30, 2024: 4.4 per million for Abrysvo and 1.8 per million for Arexvy.

The CDC didn’t mention the rates for acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, another neurological autoimmune illness seen in the original vaccine trials.

Given the limitation in the study methodology, the GBS rates probably underestimated the actual rates of the side effects. The rates are markedly lower than those in the original studies but still above the baseline in an unvaccinated population.

It’s reassuring that the vaccine appears safer than we thought last year. However, we still lack data demonstrating reduced hospitalization and death rates.

We still disagree with Pfizer and GSK’s recommendation that everyone over 60 receive the vaccine. We do agree with the CDC’s recommendations:

- Everyone aged 75 and older receive the RSV vaccine.

- People ages 60–74 at increased risk of severe RSV, meaning they have certain chronic medical conditions such as lung or heart disease, or they live in nursing homes, receive the RSV vaccine.

This recommendation is for adults who did not get an RSV vaccine last year. The RSV vaccine is not currently an annual vaccine, meaning people do not need to get a dose every RSV season.

Eligible adults can get an RSV vaccine at any time, but the best time is in late summer and early fall, before RSV usually starts to spread in communities.

Influenza Vaccine

No controversy here. We have solid evidence that influenza vaccination reduces the risk of illness, hospitalization, and death for children and adults. Therefore, we recommend it for everyone.

We recommend that you wait until October to receive your influenza vaccination. A slight delay ensures the vaccine’s three to four months of peak protection come a bit later into the flu season, which peaks late in California and can last through April/May.

However, if you plan to travel in October, receiving the vaccine in September is okay to ensure adequate time to respond to the vaccine before traveling.

This year, we have a supply of Flublok, our preferred influenza vaccine for those under age 65 or anyone allergic to traditional vaccines. We prefer Flublok over other quadrivalent vaccines because it’s less allergenic (not grown in eggs) and more potent (it contains more hemagglutinins than the standard quadrivalent flu vaccines offered in pharmacies).

As in previous years, we have the Fluzone High-Dose vaccine for individuals 65 and over or immunocompromised.

COVID Vaccine

The CDC has transitioned its COVID vaccine program to resemble that of influenza, with an annual booster recommended in the fall based on the most current circulating variant.

We agree with this approach. Unfortunately, COVID isn’t going to disappear. But as humans acquire immunity from repeated infections and vaccinations, the disease’s severity will diminish over time.

Unfortunately, COVID infection still represents a risk for stroke, heart attack, long COVID, hospitalization, and death. Those at higher risk represent most of COVID’s bad outcomes.

We differ from the CDC in assessing who should receive an annual COVID vaccine booster.

The CDC recommends an annual booster for everyone over six months of age. Because autoimmune complications of COVID occur more often (but still rarely) in young people and bad outcomes occur more in older people, we recommend the annual booster for those who are over fifty or have risk factors for a bad outcome.

These risk factors include a prior history of severe COVID infection, heart or lung disease, obesity, cancer, and diabetes. Get in touch with us if you’re unsure of your status.

The West Coast is seeing a surge in COVID cases. Many of you had COVID over the summer. A COVID infection exposes your immune system to the most current COVID variant.

If you had COVID recently, you can wait (at least) three months before receiving a COVID vaccine. Your COVID infection will give you an immune boost.

The 2024–2025 COVID vaccine targets the KP.2 strain, a great-great-great-etc.-grandson of the Omicron variant. The vaccine will be available at local pharmacies in the next few weeks and comes in three forms:

- Moderna mRNA vaccine

- Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine

- Novavax protein subunit vaccine

The CDC has approved all three.

The Novavax vaccine has been associated with fewer side effects, but the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines have more robust evidence of efficacy.

If you’ve had a particularly bad reaction to a mRNA vaccine, we recommend a Novavax vaccine. Otherwise, choose from the mRNA vaccines. You don’t need to choose the same manufacturer as you did for previous boosters.

Receiving Multiple Injections at Once

Emerging data shows that receiving an influenza and COVID vaccine simultaneously doesn’t cause appreciably more side effects and can reduce the total amount of time feeling “off,” meaning you can get all your vaccines in one sitting and “just get it over with.”

On the other hand, because the RSV vaccine is new and we’re still learning about its side effects, we don’t recommend combining it with other vaccines.

In Summary

For RSV, if you’re over seventy-five or over sixty years old and at higher risk, please receive the vaccine. We define high-risk as having a compromised immune system due to illness or medication, current cancer treatment, or a severe illness affecting your kidneys, heart, or lungs. If you are uncertain about your status, contact us. Most pharmacies have the RSV vaccine available by appointment.

For influenza, please wait until October to ensure your maximum antibody levels remain effective throughout flu season. You can be vaccinated at a pharmacy or in our clinic later in the fall. It’s okay to receive the flu vaccine in September if you plan to travel in October. Contact our office directly to schedule your flu shot.

The 2024–2025 KP.2 variant vaccine for COVID will be available soon. Please get this vaccine if you are over fifty years old or have risk factors for a bad outcome. If you recently had COVID or an earlier COVID vaccination, you can wait three months before getting this vaccine. Our office will not have the COVID booster; please contact your local pharmacy to set up a COVID vaccine appointment.

Best of Health,

Dr. Waheeda Hiller

Dr. Lindsay Klein

Dr. Barry Rotman

Alcohol and Your Brain: The Long-Term Impact on Thinking and Memory

We’ve all had too much to drink and regretted that decision. But what are the long-term effects of alcohol on the brain? Can you mitigate those effects?

What Is Alcohol Brain Fog?

Alcohol brain fog is any cognitive difficulty you experience during or after ingesting alcohol. Those may be difficulties with focus, memory, coordination, concentration, or judgment.

It’s a broad definition, so we’ll divide it into three categories of effects: immediate, day after, and long-term.

Alcohol’s Acute Effects on the Brain

Alcohol’s Acute Effects on the Brain

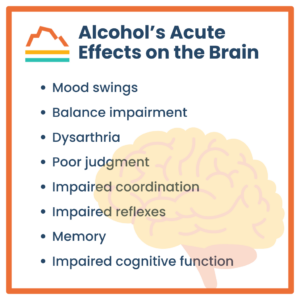

Acute ingestion of alcohol (aka being drunk) has all sorts of consequences because of direct chemical effects on the brain, including:

- Mood swings

- Balance impairment

- Dysarthria

- Poor judgment

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired reflexes

- Memory

- Impaired cognitive function

If the amount of alcohol in your bloodstream reaches toxic levels, you can overdose, which can be fatal. High alcohol concentrations can cause loss of consciousness, temperature dysregulation, impaired breathing, and heart failure.

Acute alcohol ingestion also has a high mortality risk because of direct toxicity and associated behaviors. For example, drunk people are much more likely to die because of falls, motor vehicle accidents, and fights. In 2022, 32% of all driving fatalities were a result of alcohol-impaired driving.

Sex and alcohol don’t always pair well, either. Of the 25% of women who have been victims of sexual assault (a conservative estimate), half of those cases involved alcohol consumption by the perpetrator, the victim, or both.

Why Does Alcohol Consumption Lead to Bad Decisions?

Alcohol increases the sedative effects of the neurotransmitter GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid), which blocks certain signals from the central nervous system. It also dulls the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate, which plays a key role in learning, memory, sleep, and mood.

Alcohol also enhances dopamine, leading to the euphoria associated with alcohol consumption.

Finally, alcohol disrupts communication between the brain’s neurons, which causes more global side effects like loss of balance, memory, speech, and judgment.

The Next-Day Effects of Alcohol on the Brain

The day after you drink, you may experience a hangover, among other symptoms.

Alcohol is a diuretic, meaning it causes fluid loss in the body. It makes you thirsty, dehydrated, and susceptible to electrolyte imbalance. Unless you correct the problem, you’ll likely experience weakness, headache, dizziness, and cognitive impairment.

Alcohol can also interfere with the production and metabolism of glucose, leading to low blood sugar, fatigue, and mood and cognitive changes.

It can also disrupt sleep — a separate pathway for cognitive impairment. If drinking too much ruins your sleep, you may wake up with a double dose of brain fog.

Even after a single day of drinking, you may experience a mini-withdrawal effect. You may feel restlessness and anxiety associated with levels of alcohol in the brain.

Long-Term Effects of Alcohol on the Brain

Alcohol is a neurotoxin. That means that after enough exposure, it shrinks both individual neurons and the entire brain. When particular regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, are chronically exposed to alcohol, memory, mood, behavior, and cognition suffer.

When you ingest enough alcohol over time, it interferes with the absorption of the B vitamin thiamine because your body uses the thiamine to metabolize alcohol. This leads to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, which is associated with mental confusion, memory, and eye movement disorder.

Chronic alcohol use leads to alcohol use disorder, which is associated with cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Alcohol use disorder can exacerbate underlying concomitant depression and anxiety.

Perhaps most distressing, alcohol use in children and young adults can arrest or impair the completion of brain development and can lead to long-term brain impairment. This remains true even after they stop ingesting alcohol.

How Can We Minimize Alcohol’s Effects?

Or, more specifically, how can we minimize alcohol’s effects relative to the three time spans we discussed above (immediate, next-day, and long-term)?

Immediate

Be cautious about your consumption rate. We consider the “standard drink” to be 12 oz. of beer, 5 oz. of wine, or 1.5 oz. of distilled spirits per hour. However, every pour is highly variable.

There’s also variability in individual susceptibilities. Women tend to weigh less than men and are enzymatically prone to not processing alcohol as quickly. Therefore, they’re more likely to feel the acute effects of alcohol sooner.

Food slows alcohol absorption. Staying hydrated also helps mitigate adverse effects.

As for other side effects of drinking, like poor judgment, it’s best to plan ahead. Don’t drink yourself into oblivion. Take an Uber home. Make sure you’re with people you trust. Don’t let alcohol lead you anywhere unsafe.

Next-Day

Eating and drinking will help with a hangover. Electrolytes are best. Coffee or tea can also help in moderation.

Expect your sleep to be impaired, so sleep in or take a nap if you can.

Long-Term

There’s no safe way to be a chronic heavy drinker. The best thing to do is seek help.

Today’s Takeaways

Alcohol can be enjoyed in moderation, and there are ways to mitigate the effects of overindulging. However, excessive drinking is dangerous, especially for young people.

If you need help cutting alcohol out of your life, we’re here to help and would be happy to talk. Schedule an appointment today.

What You Need to Know About Regional Steroid Injections and Alternatives

I see many patients eager to treat their painful joints with regional steroid injections. I urge them to weigh the risks and benefits carefully. Like all things in medicine, one size does not fit all, and alternatives to mainstream treatments are often safer and more effective in the long run.

Below, I’ll explain how regional steroid injections work, why doctors use them, why they’re not my first treatment choice, and what alternatives I recommend.

What Is a Regional Steroid Injection?

Corticosteroids, also called glucocorticoids, are injected directly into a specific affected area of the body to reduce local inflammation and relieve pain. Examples include shoulder and knee joints or the epidural space surrounding the nerves in the neck and back.

These injections’ effects are variable, ranging from no response to pain relief lasting from a few weeks to a few months.

Why Doctors Administer Steroid Injections

Administering a glucocorticoid regionally (as opposed to orally or injecting it into the bloodstream) exposes only a small part of the body to the drug and reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of system-wide side effects. However, even local side effects are possible.

The most common side effects that can occur at the injection site include:

- Hypopigmentation (loss of pigmentation)

- Joint infection because of reduced immune function

- Worsening of the adjacent bone’s integrity

- Atrophy (weakening of tendons, ligaments, and muscle in the region)

Can Local Steroid Injections Affect the Entire Body?

Yes, depending on the individual and the amount and type of glucocorticoid injected.

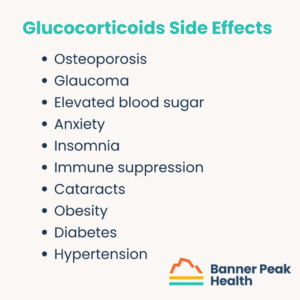

Glucocorticoids are a double-edged sword. They relieve pain, but they have a long list of detrimental side effects throughout the body. These include:

- Osteoporosis

- Glaucoma

- Elevated blood sugar

- Anxiety

- Insomnia

- Immune suppression

- Cataracts

- Obesity

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

These side effects could occur in the short term or long term, depending on the amount of drug injected and the exposure duration. The fewer glucocorticoids you expose your body to, the better.

Some demographics are at a higher risk of experiencing these side effects, including:

- Children — steroids can stunt growth

- People with osteoporosis — steroids can exacerbate the disease

- Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding — drugs can pass to the fetus

- Athletes — steroids injected near tendons or ligaments can increase the risk of rupture

- People with diabetes — steroids can cause sudden, extreme blood sugar spikes

- People with compromised immune systems — steroids can further compromise the immune response

- People prone to neuropsychiatric side effects (i.e., anxiety) — steroids can produce an acute anxiety response

There’s a movement afoot within the medical community to reformulate glucocorticoids so that they absorb more slowly. This would have two benefits:

- It keeps the drug in the joint longer, extending its effects (inflammation reduction and pain control).

- It’s a lower dosage, providing longer-lasting effects with less drug absorbed into the body.

Are There Alternatives to Steroid Injections?

Steroid injections are a Faustian bargain.

If you’re unfamiliar with the reference, Dr. Faustus is a character from a medieval German play. In the play, he trades his soul to the devil for unlimited knowledge.

Steroid injections may not be as malicious as the devil himself, but the trade for pain-free joints is risky.

If the risks aren’t worth it to you, you have a wide range of alternative solutions to choose from. I recommend the following:

- Topical NSAIDs (including diclofenac)

- Non-pharmacological remedies

- Resting the joint

- Physical therapy

- Massage

- Chiropractic care

- Acupuncture

Today’s Takeaways

I’m not a fan of steroid injections. They present a considerable amount of risk for the benefit they offer. Alternative treatments may provide benefits with far less risk.

Talk with your doctor, consider the risks, and explore all the options before choosing a safe route to healing.

How Long Does Blood Pressure Medicine Take to Work?

Patients with hypertension often ask, “How long does blood pressure medicine take to work?”

It depends. Most blood pressure medications take a few long weeks to reach their full effect — but there are steps you can take to lower your blood pressure in the meantime.

How High Blood Pressure Affects the Body

To understand how blood pressure medication works, you first need to understand what causes hypertension (high blood pressure).

Think of your blood vessels as an old-fashioned mechanical watch — one with dozens of interconnected gears and springs. When a single part malfunctions, the disruption spreads to other parts of the system, and the watch eventually stops working.

Repairing that one part triggers a chain reaction throughout the entire system, and the watch works better than it did before.

For a deeper exploration of blood pressure and its effect on the body, check out my blog post: A Physician’s Experience With High Blood Pressure.

How Long Does Blood Pressure Medicine Take to Work?

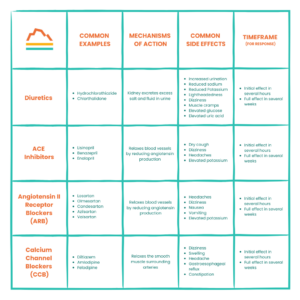

There are four common categories of blood pressure medication, but they all work within similar time frames. The initial effect occurs within hours but doesn’t reach its full effect for two to four weeks.

The following table describes the four common types of blood pressure medication, their mechanisms of action, and common side effects. The medication your doctor prescribes depends on your individual characteristics and risk factors:

How to Improve Your Medication’s Effectiveness

When your blood pressure is high, you want to lower it as quickly as possible. Making healthy lifestyle changes can boost your medication’s performance and reduce your blood pressure before your medication takes full effect.

Important: Lifestyle changes are not a replacement for professional help. If you have high blood pressure, you NEED to work with your doctor to lower it. Take your prescribed medication and follow your doctor’s advice.

While you’re doing that and waiting two to four weeks for your medication to reach its full effect, you can also (with your doctor’s approval!) make the following changes at home:

Reduce or Eliminate Unhealthy Foods and Substances

Some foods, drinks, and substances are notorious for elevating blood pressure. These include nicotine and alcohol.

Caffeine may be beneficial for some, but it can harm individuals with hypertension. While studies are still in progress, it’s best to reduce or eliminate your caffeine intake if your blood pressure is high.

Although sodium is necessary, excess salt is not. In the United States, virtually everything packaged, canned, frozen, processed, or served in a restaurant contains too much salt for someone with high blood pressure. Avoid excess salt by cooking fresh food at home or looking for foods with low sodium.

Adopt DASH

DASH (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) is a diet clinically demonstrated to lower blood pressure. The diet includes fresh fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and low-fat dairy.

Exercise

Exercise is the closest thing we have to magic. Studies show that exercise, specifically strength training, for a minimum of 150 minutes per week can improve blood pressure independently of weight loss.

Weight Loss

While not everyone with high blood pressure needs to lose weight, many do. Losing just 5–10% of your body mass can profoundly impact your blood pressure if you’re overweight.

Losing weight when necessary can also improve other factors that contribute to high blood pressure, like sleep quality.

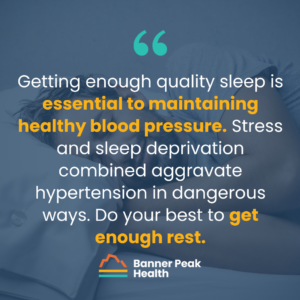

Sleep

Getting enough quality sleep is essential to maintaining healthy blood pressure. Stress and sleep deprivation combined aggravate hypertension in dangerous ways. Do your best to get enough rest.

(If you aren’t getting enough sleep and need help figuring out why and how to improve your sleep quality, reach out today to discuss your options.)

Stress Reduction

We all know stress is the enemy of good health, but it’s especially insidious toward blood pressure.

Tackling your stress doesn’t have to be a chore. It can be as simple as reducing certain environmental noises with noise-canceling headphones or a white noise machine or meditating for a few minutes before hitting the hay. Spending time in nature has also been shown to reduce stress.

There are many ways to modify your environment and your lifestyle to reduce stress — you just need to find those that are most effective for you.

Today’s Takeaways

Now that we’ve answered the question, “How long does blood pressure medicine take to work?” and explored other ways of lowering blood pressure, the ball is in your court.

Follow your physician’s advice, take your medication as prescribed, and remember that there’s more to lowering blood pressure than taking a pill.

What Do Studies Show About the Relationship Between Stress and Memory?

Can you remember a stressful experience you had years ago with amazing clarity, but not what you had for dinner last night?

There’s a scientific reason!

Stress exposure directly impacts memory formation and retrieval. Sometimes, that’s helpful, and other times, not so much.

So, what do studies show about the relationship between stress and memory?

What Do Studies Show About the Relationship Between Stress and Memory?

Many studies explore how stress affects memory encoding and retrieval. The literature can appear contradictory.

To provide better clarity, I’ll break this topic down into three sections:

- How the timing of stress exposure affects memory formation and retrieval

- The body’s cortisol response

- Individual variation

How Does the Timing of Stress Exposure Affect Memory Formation and Retrieval?

We categorize stress into two groups: acute stress and chronic stress. Each triggers unique physiologic responses.

During acute stress (stress that occurs over the course of minutes or hours), memory is enhanced. According to the current theory, because your body’s cortisol levels spike during stress, brief spurts of cortisol enhance memory function.

This makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. Consider what caused stress in cavemen (stumbling upon a lion’s den, for example) and why it was important to remember that information (so they could avoid that den in the future).

Chronic stress (ongoing stress over days, weeks, months, or longer) is different. When endured at high levels over time, cortisol becomes a neurotoxin. Although it’s our own hormone, it can damage vital parts of the brain, including the hippocampus, the region responsible for memory formation and processing.

To put things simply, acute stress helps both memory encoding and retrieval, and chronic stress hurts both memory encoding and retrieval.

How Does the Body’s Cortisol Response Influence Memory?

The memory formation and retrieval process is multi-layered, leaving many opportunities for individual variations.

The first layer is our hormonal stress response. This includes the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which determines how much cortisol the body secretes.

The second layer is how our brains function, including the size of different parts of the brain, which varies tremendously. These size variations determine how the hormonal stress response signal reaches the brain and how strong it is when it gets there.

The third and final layer is individual traits and personal history. For example, someone who’s been clinically diagnosed with anxiety or depression has a cortisol response that’s more highly attuned to their memory. Also, someone who has a history of trauma or PTSD has a more intense stress response, which also impacts their memory.

These three layers combined create the potential for tremendous variation in the relationship between stress and memory. This means that the same stress level can impact each person differently.

Physiological Presentations of Stress Depend on the Individual More Than the External Stressor

It’s easy to believe that a high-stress situation, such as a shootout with the police, would trigger a more severe biological response than a lower-stress situation, like watching a horror movie. However, that’s not always the case.

An individual’s stress response depends on the physiological variations I explored above. Take a man with PTSD, for instance. Watching “Saving Private Ryan” may trigger flashbacks and an elevated heart rate, but if his wife suffers a sudden heart attack beside him, he may remain calm, cool, and collected as he administers life-saving care and calls for help.

In other words, the factor that most influences the way stress presents is not the external trigger of the stress — it’s the person experiencing the stress.

This makes studying stress’s effects on memory challenging.

How to Mitigate Stress’s Negative Effects on Memory

Regardless of your individual variations, you can limit and improve stress’s effect on your memory by making healthy lifestyle choices.

I’ll sound like a broken record, but here are the best ways to help reduce stress and maintain or improve your memory formation and retrieval:

- Exercise regularly

- Consume a healthy diet

- Avoid unhealthy substances

- Get proper sleep

- Socialize

Here’s why these recommendations are vital:

Exercise

Studies demonstrate that exercise reduces stress and improves cognitive function.

“Neuroplasticity” refers to the brain’s ability to change through growth and reorganization. We used to think that young people’s brains would create new connections between neurons, and those connections would mature as they became young adults and remain the same for life.

Now, we’re realizing this isn’t the case.

Given the right conditions, we may be able to create new neural pathways throughout our lives. One condition is exercise, a method for improving hippocampal function. Since the hippocampus is intimately involved in memory function, there is evidence that exercise can help improve memory.

Diet

Diet choices, including consuming healthy fats, can also improve memory.

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, flax seed, oil, and nuts, are an excellent source of healthy fats. Monounsaturated fats like olive, avocado, and various nut oils are also great.

Interestingly, fiber is also associated with improved memory function. We’ve come to understand that our gut microbiome affects almost every aspect of our health and that there’s a gut-brain connection. So, eating a bowl of oatmeal for breakfast might just help you ace that exam.

Unhealthy Substances

In case you needed another reason to avoid substances like nicotine and alcohol, studies demonstrate that they hurt memory formation and retrieval.

Caffeine, however, is not detrimental to memory. But using caffeine to compensate for poor sleep habits is like smacking a Band-Aid on top of a gaping wound.

Sleep

I’m always talking about the importance of sleep. Sleep is highly associated with memory function and stress reduction, which also improves memory.

So, try improving your sleep hygiene. It’ll improve your alertness more than that second pot of coffee.

Socialization

Decreased socialization and loneliness correlate with stress and an increased risk for dementia and impaired memory. Social interactions can help.

Therapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, can also reduce stress and improve memory function. So can mindfulness meditation.

Regarding Physical or Mental Illness

If you’ve been diagnosed with anxiety, depression, PTSD, or other mental or physical illnesses, talk with your doctor or seek other medical attention before making any changes to your routine, especially if you take medications.

Today’s Takeaways

We began this post by asking, “What do studies show about the relationship between stress and memory?” We’ve covered that and more:

- How stress can affect your memory

- How stress can affect your body

- How to address stress in a healthy way

If you need help managing your stress or have concerns about your memory function, reach out today. We’re here to help.

Can You Drink Coffee While Fasting? How to Do It the Right Way

My patients often ask me, “Can you drink coffee while fasting?”

My response is, “It depends. Why are you fasting?”

Fasting can mean many different things, so before I explore whether you can drink coffee while fasting, let’s define “fasting.”

Types of Fasting

Fasting means not eating for a period of time. This abstinence can also include drinking, depending on the type of fasting you’re partaking in.

For example, the Jewish faith defines fasting (such as for Yom Kippur) as going without food and drink (including water). When my Jewish patients schedule a fasting blood test, I need to remind them that they can drink water. It’s harder to draw blood from a dehydrated patient.

For medical purposes, such as blood draws, we at Banner Peak Health define fasting as abstaining from food for at least 12 hours, but drinking plenty of water is encouraged. This is similar to intermittent fasting, which many people practice as a weight loss method.

Drinking Coffee During Intermittent Fasting

When drinking coffee during an intermittent fast, the devil is in the details. In other words, it depends on what you add to your coffee.

Black coffee is fine since it only contains two to five calories per cup. However, once you add cream and sugar, the calories increase quickly:

- One teaspoon of sugar = 16 calories

- One pump of sweetened creamer = 10–20 calories

- Two teaspoons of whipped cream = 73 calories

- Two teaspoons of half & half = 40 calories

- Two tablespoons of non-dairy creamer = 20 calories

- Two tablespoons of oat milk = 15 calories

Benefits of Drinking Coffee During a Fast

It’s true — drinking coffee can be beneficial while fasting.

Coffee is a mild appetite suppressant, meaning it can fight hunger. It also increases alertness and combats caffeine-withdrawal headaches.

However, if a lack of caffeine causes headaches, you may want to consider why you need so much of it in the first place (e.g., are you getting enough sleep?).

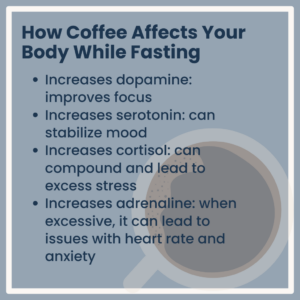

How Coffee Affects Your Body While Fasting

Coffee consumption impacts your hormone levels:

- Increases dopamine: improves focus

- Increases serotonin: can stabilize mood

- Increases cortisol: can compound and lead to excess stress

- Increases adrenaline: when excessive, it can lead to issues with heart rate and anxiety

Today’s Takeaways

The question “Can you drink coffee while fasting?” has no simple answer. It depends on why you’re fasting and what you like to put in your coffee.

Ultimately, if your fasting allows for drinking and your coffee doesn’t contain added cream, milk (dairy or plant), or sugar, enjoy it.

If you’re preparing for a blood draw, skip the Frappuccino for now.

Can Stress Cause Acid Reflux?

We’ve all heard the warning that stress causes ulcers. But is that true? Can stress cause acid reflux, ulcers, and an upset stomach?

It’s true! Your grandpa was right!

Today’s research demonstrates that people experiencing chronic stress are almost twice as likely to experience GERD symptoms. But how does it happen?

How Stress Impacts the Body

Stress has a huge physiological impact on the body.

In previous blog posts, I explained how stress affects heart rate, heart rate variability, and blood pressure. These indicators are functions of the autonomic nervous system, which comprises the sympathetic nervous system. This system mediates the fight-or-flight responses.

We also have a parasympathetic nervous system that mediates our rest and digest responses. To stay healthy, we need to keep these responses balanced. If these systems fall out of balance, disease is likely.

For example, in stressful situations, the sympathetic nervous system overwhelms the parasympathetic nervous system, impairing the digestive system. The result is that digestion slows down, and food backs up in the stomach and reverses direction.

Additionally, stress enhances our sensation of belching, bloating, and digestive discomfort due to hypersensitization of the nervous system. Stress increases the amount of acid produced in the stomach, which changes the content of the gut microbiome. This can cause or add to gastronomic symptoms.

This leads to a logical question: Why doesn’t all this excess acid digest our stomach lining?

While our stomach ordinarily contains a host of protective mechanisms, such as prostacyclin signaling, stress impairs their production. As a result, prolonged stress increases the risk of damage to the stomach lining, including ulcers and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

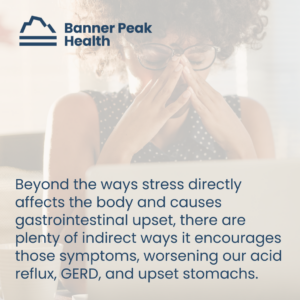

Other Ways Stress Can Cause Acid Reflux

Beyond the ways stress directly affects the body and causes gastrointestinal upset, there are plenty of indirect ways it encourages those symptoms, worsening our acid reflux, GERD, and upset stomachs.

Stress alters our behavior, and people under stress often make bad choices. They drink more alcohol, smoke more nicotine, and eat more “comfort food,” which usually contains more sugar and unhealthy fats. All these choices increase the risk of acid reflux, GERD, and stomach upset.

Are There Risk Factors for Acid Reflux?

Yes. Certain lifestyle choices increase your risk of acid reflux. These include:

- Alcohol consumption

- Nicotine use

Also, consider these other risk factors:

- Elevated body mass index (BMI), specifically intra-abdominal obesity

- Hiatal hernias

- Pregnancy

- Medications, including NSAIDs

How to Manage Stress and Acid Reflux

Since stress has a direct biological impact on the digestive tract, it’s worth reducing it as much as possible. Focus on the most impacted aspects of your life, such as your sleep and exercise routines. Improving these is often the best way to reduce stress fast.

Sometimes, professional help is required, too. Stress’s impact often manifests as physical symptoms, such as stomach pain. If you can’t resolve these symptoms alone, don’t hesitate to seek help from a professional, whether that be your physician or a therapist.

Your mental health and your physical health operate hand in hand.

Today’s Takeaways

If you remember nothing else from this blog post, remember this:

You asked, “Can stress cause acid reflux?”

The answer is, “Yes. It does.”

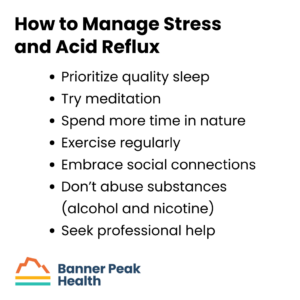

The best thing you can do to improve your acid reflux is to manage your stress level. I’ve written about this extensively, but here are some quick tips:

- Prioritize quality sleep

- Try meditation (here’s a cheat sheet!)

- Spend more time in nature

- Exercise regularly

- Embrace social connections

- Don’t abuse substances (alcohol and nicotine)

- Seek professional help

As always, we’re here to help if you need us, and our blog is full of tips for improving your health and well-being.