From Access to Optimization: The Evolution of Concierge Medicine

In July of 2007, I proudly became the second concierge medical doctor in Contra Costa County, California, pioneering a new way to bring high-quality care to patients. At the time, patients valued concierge medicine for its same-day care and after-hours phone calls.

My practice grew, and my patients were happy. For a while, running a successful practice was enough to satisfy me.

Over the past 18 years, I’ve watched the concierge medicine model evolve to become more widespread and accepted. At Banner Peak Health, I’ve helped drive that evolution toward what I call concierge medicine 2.0.

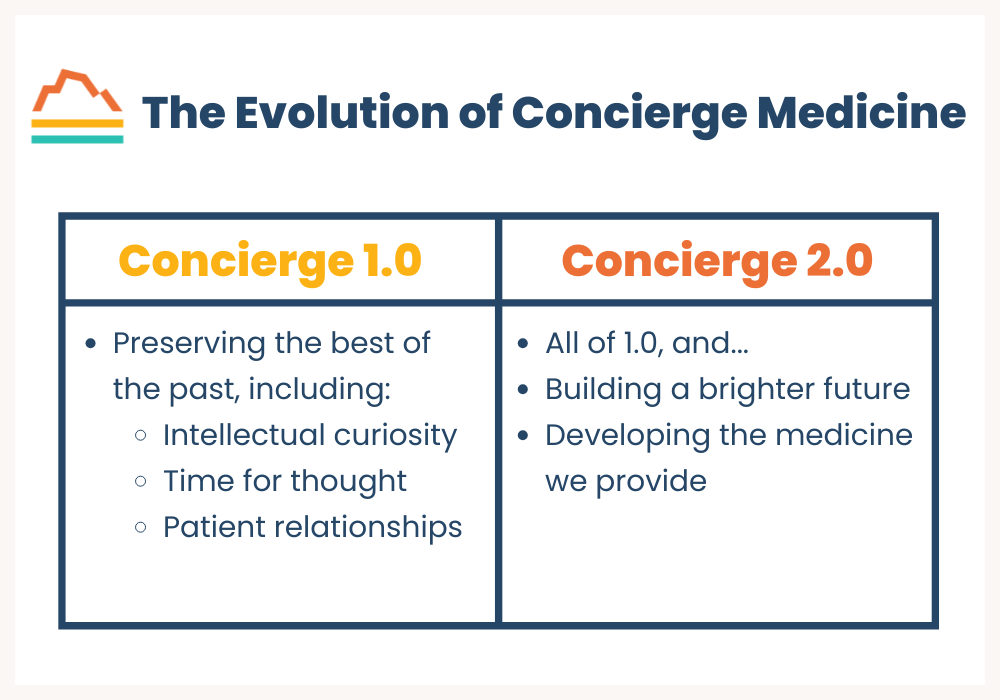

Concierge Medicine 1.0

Concierge medicine 1.0 is high-quality medical care that prioritizes patients and is not beholden to insurance companies. It preserves the golden era of medicine by prioritizing the patient-doctor relationship and upholding medicine’s core values:

- Patient rights

- Intellectual inquiry

- Patient-doctor bonding

- Differential diagnosis

Concierge medicine 2.0 moves beyond merely preserving the best traditions of medicine and develops new techniques to move healthcare forward.

Concierge Medicine 2.0

The concierge medicine model is appreciably different from fee-for-service healthcare. While 1.0 is high-quality internal medicine, 2.0 involves access to new technology and techniques unavailable in any other system.

At Banner Peak Health, we have access to diagnostic modalities not covered by insurance and labor-intensive treatment opportunities, which many traditional fee-for-service physicians can’t offer.

These treatments include:

- Galleri cancer screening, a simple blood test that can detect 50+ types of cancer.

- Coronary artery calcium score, a more accurate means of detecting heart disease risk than cholesterol alone.

- InBody scan, a complete body composition scan more accurate than BMI.

- SleepImage device, a comprehensive sleep study done at home with simple, precise technology.

- Labor-intensive testing techniques, which traditional healthcare lacks the bandwidth to offer. These include continuous glucose monitoring, the Oura Ring, and heart rate variability (HRV) measurement.

These advancements allow Banner Peak Health to provide personalized, direct, state-of-the-art care.

Looking Ahead

In recent years, we’ve seen an explosion in both FDA-approved and non-FDA-approved medical technology. My challenge and privilege is guiding my patients through the labyrinth of options.

The concierge medicine 1.0 model still struggles with bandwidth, though not as much as traditional healthcare. However, concierge medicine 2.0 facilities like Banner Peak Health are able and determined to better meet members’ needs.

As we move into the latter half of the 2020s, expect an increase in the prevalence of consumer wearables, like the Oura Ring. We expect manufacturers to develop and distribute these outside the medical industry, but we’ll break down silos and continue to identify and validate medical applications.

For example, sports medicine pioneered techniques for measuring and monitoring heart rate variability, but we now understand its relevance in internal medicine.

Today’s Takeaways

Concierge medicine 1.0 is superior to conventional (insurance-based) healthcare. However, at Banner Peak Health, we always want to push forward. We’re proud to offer concierge medicine 2.0, and we’ll continue to expand our practice.

Unlock Your Potential: How to Naturally Boost Testosterone Levels

Every time I see a commercial for testosterone replacement, I cringe.

The United States is one of just two countries that permit direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising (the other being New Zealand). As a physician with almost four decades of medical experience, I find it concerning that Congress believes 60 seconds of information delivered to a non-professional should influence my prescribing decisions.

It’s through this lens that I consider the surge in men seeking testosterone therapy.

The Challenge With Self-Diagnosis

Advertisements promoting testosterone therapy paint a broad picture: mood swings, depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, mental fog, fatigue, reduced sex drive, increased body fat, decreased muscle mass, sleep problems — what man hasn’t experienced some of these symptoms at some point?

From 2003 to 2013, testosterone prescriptions increased fourfold for men aged 18–45 and threefold for men aged 56–64. The rates keep climbing. “Men’s health clinics” — often just testosterone prescription centers — have multiplied across the country.

If someone’s only tool is a hammer, they’ll treat everything like a nail. Yes, some men have low testosterone and would benefit from replacement therapy. But many others could naturally boost testosterone levels by addressing underlying causes.

For instance, I recently saw a patient — a healthy man in his 40s — whose testosterone levels dropped after a weekend of heavy drinking and poor sleep. His first instinct was to ask me about testosterone replacement options rather than examining his habits.

The Leaky Roof Problem

Think about a leaky roof. Your body not producing enough testosterone is like that roof leak. You have two options: put on a raincoat or fix the leak.

In this case, testosterone supplementation is the raincoat, and addressing the root causes of low testosterone is fixing the leak. The raincoat might keep you dry, but wouldn't you rather repair the roof?

Why Your Testosterone Might Be Low

Low testosterone stems from two main types of hypogonadism — a medical term for when your body isn’t producing enough testosterone. Basically, something in your body isn’t optimal, and your evolutionary quality control is putting the brakes on reproduction.

In other words, Charles Darwin doesn’t think you should have kids right now.

Primary hypogonadism occurs when your testicles can’t produce enough testosterone on their own. Think of it like a factory that’s lost its manufacturing capability. This can happen due to:

- Inherited disorders

- Physical trauma to the testicles

- Hemochromatosis (iron storage disease)

- Cancer treatment side effects

Secondary hypogonadism is more common. Here, the problem lies with your brain’s signaling system — the hypothalamus and pituitary gland don’t send proper signals to tell your testicles to make testosterone.

This can result from:

- Abnormal hormone levels, like prolactin

- Iron storage disorders affecting the pituitary gland

- HIV/AIDS

- Thyroid disease

- Chronic pain medication use

- Type 2 diabetes

- Kidney disease

- Liver disease

- Lung disease

- Sleep apnea

- Steroid medications

- Alcohol overuse

- Severe stress

- Nutritional gaps

- Too much or too little exercise

Nature’s Warning Sign

Low testosterone acts like a canary in a coal mine — a warning that something needs attention. When your body reduces testosterone production, it’s indicating that conditions aren’t optimal for reproduction.

This signal deserves investigation, not just medication.

In fact, using testosterone or testosterone-like supplements can actually suppress your body’s natural production. Some men, particularly younger ones who misuse these substances, face permanent fertility problems even after stopping.

How to Naturally Boost Testosterone Levels

To naturally boost testosterone levels, start with self-reflection. Take an honest look at your:

- Sleep quality and quantity

- Get tested for sleep apnea if you snore

- Aim for 7–8 hours of quality rest

- Maintain a consistent sleep schedule

- Stress levels

- Build stress management habits

- Exercise habits

- Balance exercise without overdoing it — both overexercising and underexercising can lead to low testosterone

- Nutrition

- Alcohol consumption

- Medication use

- Talk with your doctor about alternatives to steroids or opioids

- Never stop medications without medical guidance

The Smart Path to Natural Testosterone Production

Some men need testosterone replacement, particularly those with age-related declines not linked to correctable conditions. However, many can naturally boost testosterone through lifestyle changes.

If you think you might have low testosterone, start by examining your habits and health. If you still feel testosterone therapy might help, work with a medical provider who will thoroughly evaluate all possible causes — one who looks beyond quick fixes to find the true source of the problem, like the physicians at Banner Peak Health.

Don’t just buy a raincoat. Fix the roof.

How Our New VO2 Master Measures VO2 Max

Testing new medical technology is one of my favorite parts of being Chief Innovation Officer at Banner Peak Health.

I’ve spent the last year researching VO2 max and Zone 2 testing devices for sports physiology. I’ve finally identified the best device for our members: the VO2 Master, made by a Canada-based company.

The VO2 Master is a portable device without external tubes or wires. Like a respirator, it fits over your nose and mouth, and integrated software connects with an app you download onto your phone or tablet. It’s sufficiently accurate in metabolic testing, and Peter Attia, author of The New York Times bestseller “Outlive,” considers it his go-to device.

When used with graded exercise testing, the VO2 Master provides a wealth of information we’ll use to understand our members’ metabolic health and athletic capacity. It also hones in on areas for improvement and helps create treatment plans.

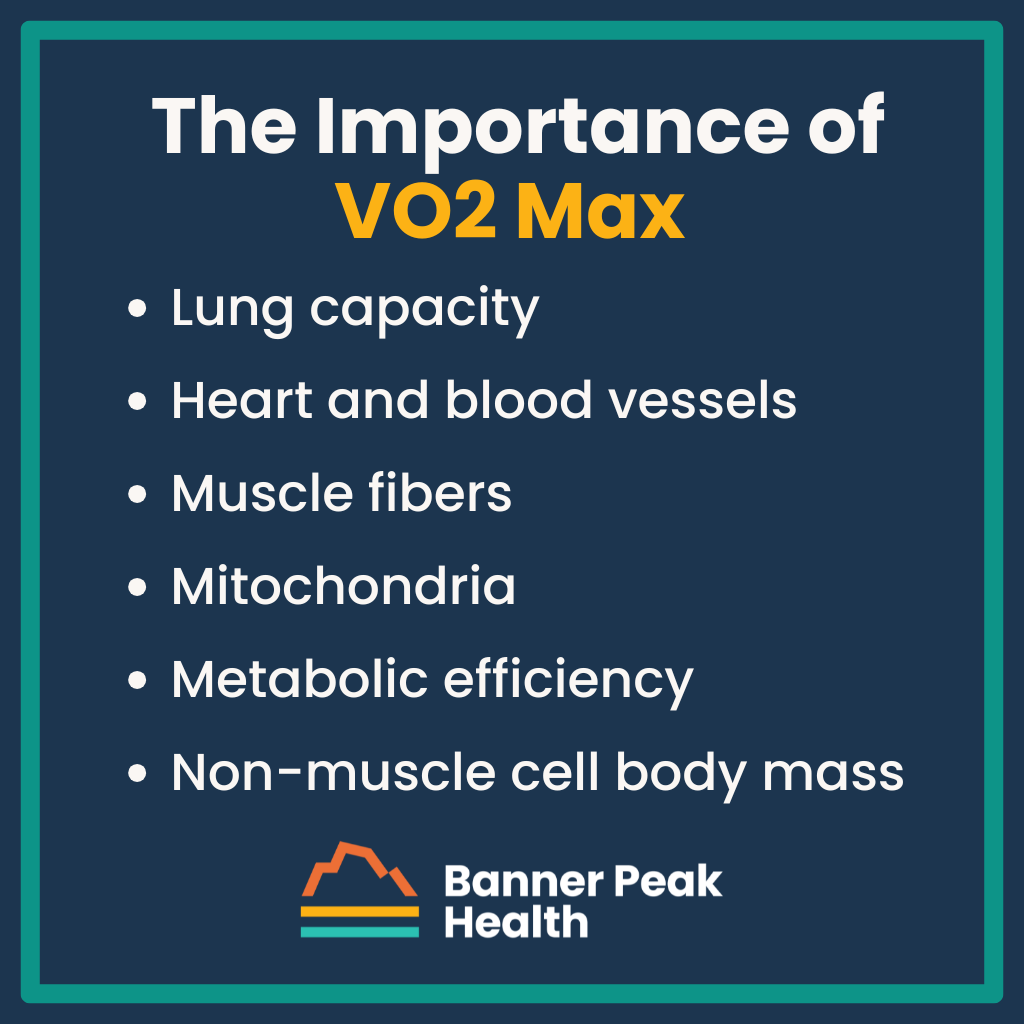

The Importance of VO2 Max

VO2 max is how much oxygen you consume per kilogram of body weight. It’s a single measurement that encompasses the function of many important bodily systems, including:

- Lung capacity: Inhaling and exhaling

- Heart and blood vessels: How efficiently and in what quantities the blood delivers oxygen

- Muscle fibers: Muscle quality and quantity

- Mitochondria: Fuel sources, like fatty acids and glucose, mix with oxygen to produce ATP for energy

- Metabolic efficiency: Insulin resistance impairs mitochondrial function

- Note: Diabetics have lower VO2 max because they can’t burn fatty acid

- Non-muscle cell body mass: Every fat cell reduces VO2 max because fat doesn’t burn oxygen

VO2 max is one of the most potent longevity predictors, a point Peter Attia makes in his book as he encourages readers to maximize their VO2 max.

The Current Challenge

Derive your VO2 max by either:

- Measuring it at maximum output

- Estimating it from other derived physiological parameters

Although many people want to know their VO2 max, only a small percentage can successfully undergo a graded exercise test (measuring it at maximum output).

Unless you have athletic training, pushing your body to its limit is difficult — even more so while wearing a gas mask. Further, individuals with risk factors for cardiovascular disease who haven’t exercised to that level of intensity risk injury.

That’s why Banner Peak Health offers a modified submax test. It doesn’t require extreme exercise, but it still estimates VO2 max accurately. Safety is our priority.

We also offer a full VO2 max test for members with prior athletic training and no risk of cardiovascular disease.

How to Improve Your VO2 Max

To improve your VO2 max, focus on your:

Lung Function

Manage any obstructive illness, such as asthma or emphysema, and tell your physician if you have a history of scarring or pneumonia.

Use techniques like belly and diaphragmatic breathing to improve air movement through your lungs.

Heart and Blood Vessels

Maintain hydration and tell your physician if you have anemia symptoms. Then, stay cardiovascularly fit through two forms of targeted aerobic training:

- HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training): Exercise involving exertion for one to five minutes at 90%–95% of your maximum heart rate, resting in between.

- Zone 2 Training: Exercise for 50–60 minutes thrice weekly at a conversational pace.

Muscle Fibers

Perform resistance training, or strength training, to increase your muscle fibers’ efficiency and quantity.

Mitochondria

Extra fat mass hormonally impairs your mitochondria’s ability to metabolize fatty acid.

Combine exercise and weight loss (reducing fat, not muscle) to reverse this and optimize mitochondrial function. Zone 2 training is particularly effective in this application.

Metabolic Efficiency

Weight loss (i.e., fat reduction) improves VO2 max since excess fat cells don’t burn oxygen. Reducing fat also improves metabolic efficiency by reducing your total kilograms of body tissue.

Looking Forward to Improvement

It’s possible to improve your VO2 max by 5%–10% in just 60–90 days. Some people have improved their VO2 max by 25% over a year.

The lower your VO2 max is now, the more room you have to improve it, and the faster that improvement may be.

VO2 Master will help you understand your health status. With that information, your Banner Peak Health team will guide you to your health and performance goals.

CPAP Alternatives: Effective Ways to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea

We lose muscle tone while we sleep, increasing the risk of our tongue falling backward and the collapse of our throat muscles.

When this happens, the result is obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) — partial or complete blockage of the upper airway, interfering with air passage to and from your lungs during sleep. This interference reduces the amount of oxygen reaching the body and brain and releases adrenaline, hindering the body’s ability to sleep.

Normal sleep physiology occurs in stages, which I’ve written about extensively. OSA disrupts these stages because of hindered breathing, causing many serious problems.

In the short term, OSA can cause poor memory, headaches, and fatigue, which may cause the patient to fall asleep while driving. Long-term complications include:

- Increased risk of obstructive airway disease

- Heart attacks and congestive heart failure

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Non-insulin-dependent diabetes

- High blood pressure

- Insulin resistance

- Atrial fibrillation

- Dementia

Obstructive Sleep Apnea’s Impact on Hormones

Obstructive sleep apnea increases the release of stress hormones such as adrenaline and epinephrine.

Beneficial hormones OSA reduces:

- Human growth hormone (HGH): Repairs and builds muscles.

- Testosterone: Maintains sexual function and healthy body composition in terms of muscle mass and fat distribution.

- Estrogen: Maintains healthy body composition and bone health.

Potentially harmful hormones OSA increases:

- Cortisol: Impairs immune function and increases the risk of obesity.

- Leptin: Decreases satiety.

- Ghrelin: Increases appetite.

Athletic Issues

Not only does OSA impair day-to-day functioning and increase the risk of long-term illnesses, but it also interferes with athletic performance in terms of strength, endurance, and cognition.

In 2013, the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine examined 12 male, middle-aged golfers with severe OSA. The golfers underwent treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP — more on this later). Then, after 20 rounds of golf, every golfer’s handicap index (HI) was evaluated.

While the non-OSA control group showed no improvement, the OSA group treated with CPAP improved by 11.3%, and the more skilled players (HI<12) improved by 31.5%.

I’m not a golfer, but I’ve worked with many and have recognized their devotion to the sport. This study proved they’ll do anything to improve their game.

Hurdles to Treatment

CPAP treatments are effective and beneficial. However, patients often hesitate to discuss their OSA symptoms with a physician because they’re afraid they’ll be prescribed a CPAP machine.

CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) is the gold standard of obstructive sleep apnea treatment. Unfortunately, for most people, it evokes Darth Vader, with a face obscured behind a large mask.

Thankfully, CPAP machines have come a long way since their inception in the 1980s. They’re no longer vacuum cleaner-esque appliances. Even the full-face models are whisper-quiet. If you can’t stand the thought of re-enacting the “Luke, I am your father” scene with your spouse every night, there are plenty of variations to choose from.

For severe OSA or mild-to-moderate OSA with risk factors for complications such as heart attack, AFib, or stroke, the first choice and standard of care is a CPAP machine. But if you suffer from mild-to-moderate OSA and a CPAP machine is off the table for you, you may benefit from an array of alternative treatments.

The Evolution of OSA Treatment

The old-school diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea required an overnight polysomnogram (at a sleep study facility) with 22 wires attached to you. If you received a diagnosis of OSA, a CPAP machine prescription followed. It wasn’t practical to repeat the sleep study to assess how well the CPAP machine worked for you.

At-home sleep studies and sleep-tracking tools (such as SleepImage) have since improved OSA treatment. These advancements allow for effortless multi-night testing in the comfort of your home, allowing a trial-and-error approach to OSA treatment. This is revolutionary, not only diagnostically but therapeutically.

Stacking Therapy Modalities

Stacking modalities means combining multiple therapies. Each individual therapy may offer only a minimal benefit, but combined together, they can provide significant improvement. Each person can experiment with combining a variety of treatments to create a successful outcome, rather than reaching for the biggest gun (i.e., CPAP) first.

At Banner Peak Health, we use SleepImage and collaborate with Empower Sleep. We also consider adding other modalities to the stack, including tools that:

- Improve nasal patency: Nasal steroids, nasal strips, and nasal dilators improve airflow through the nostrils.

- Minimize mouth breathing: Tools like external straps and tape close the mouth and encourage nasal breathing. These tools also hold the tongue in a more forward position and prevent it from falling backward as we sleep, where it might obstruct the airway.

- Improve sleep position: Pillows and wedges prevent people from sleeping on their backs. A supine (lying flat on the back) position puts a person at risk of obstruction, and gravity compounds this risk. Side sleeping helps stabilize the throat muscles so they don’t collapse and interfere with air passage in and out of our lungs.

- Improve tone and tongue position: Excite OSA and REMplenish Straw are like push-ups for your tongue. Mandibular advancement devices like myTAP and Zyppah bring the lower jaw forward. Since the lower jaw anchors the tongue, this repositioning reduces the obstruction risk by keeping your tongue clear of the airway.

- Modify airway pressure (without CPAP): Try Bongo Rx for increased expiratory positive airway pressure.

Today’s Takeaways

Sleep is the foundation of good health. That’s why Banner Peak Health stays at the cutting edge of sleep science. We’re always brainstorming new ways to maximize and optimize your sleep.

Reach out today and tell us about your sleep concerns. We’re happy to help you.

Anabolism vs. Catabolism: How to Balance Both for Healthy Weight Loss

This year, my Thanksgiving dinner table conversation included weight loss efforts. My friends and family members reported their eating and aerobic exercise habits. No one mentioned resistance training.

Resistance strength training is essential for successful weight loss. To understand why, we must first understand anabolism and catabolism.

Anabolism vs. Catabolism

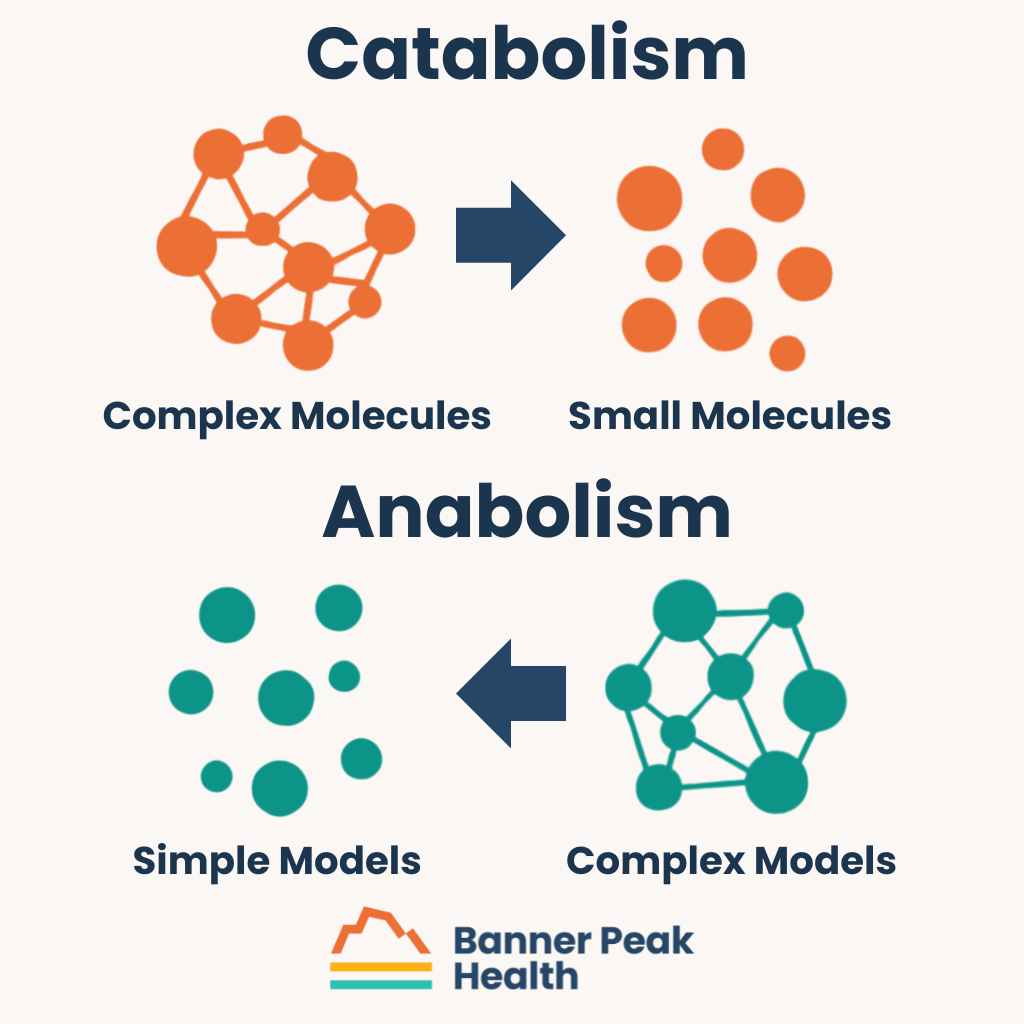

Catabolism is the process of breaking complex molecules into smaller ones to release energy as ATP, a chemical fuel for the body. ATP allows cellular functions, growth, and movement.

Anabolism builds complex models from simple ones through a process that requires ATP.

Anabolism and catabolism exist in a balance called homeostasis, which reflects the body’s metabolic condition.

Weight Loss Isn’t Just Superficial

Weight loss’s effects go beyond physical appearance. It improves almost every aspect of your health, including your health span (the number of years you enjoy optimum health).

To do that, we need to increase muscle mass and reduce fat tissue. How we lose weight determines what happens to those two components.

In traditional caloric restriction dieting, we consume fewer calories than our bodies metabolize, i.e., the body eats itself. When this happens, about 25% of weight loss comes from muscle and 75% from fat. For example, if you lose 10 pounds, 2.5 pounds will be muscle, and 7.5 pounds will be fat.

Fat cells are endocrinologically active. They skew our bodies metabolically in negative ways, and we want to get rid of them.

Muscle cells skew our bodies positively. Losing muscle puts some people at risk for sarcopenia — a lack of adequate muscle mass.

Muscle Mass and Metabolism

The body metabolizes (i.e., burns up as energy) 70–90% of its glucose in the muscle cells. The more muscle cells we have, the more adequate our glucose balance and quantity, and the healthier we are.

Muscle mass is how we:

- Preserve function, including our ability to move and perform tasks, and our ability to stay strong and balanced to reduce fall risk

- Preserve our quality of life

- Preserve and extend our life expectancy

As we age, we produce less hormones involved in muscle maintenance, such as human growth hormone and testosterone. People also tend to do less weight-bearing exercise as they age, so the muscles receive less stimulus to maintain their mass. And as we age, anabolic resistance (where it becomes harder for the muscles to build up from anabolic processes) makes it harder to maintain muscle mass.

Think of muscle mass as money in the bank. We invest our money early to ensure a comfortable retirement decades later. In the same way, lay down muscle mass when you’re young and energetic so it’s there to maintain later.

Balancing Anabolism and Catabolism

This brings us back to anabolism and catabolism.

You lose muscle mass if your body skews toward catabolism. Be exceptionally careful during that catabolic process to maintain muscle mass. Otherwise, you risk sarcopenia.

The Dangers of Weight-Loss Drugs

You’ve probably heard of a new, powerful class of weight-loss drugs, including Wegovy, Mounjaro, and Ozempic.

These GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide and liraglutide) induce such strong catabolic states that they’re associated with 10–40% of weight loss as muscle mass. This happens because:

- Your body is strongly catabolic, breaking down lots of tissue.

- You’re making behavioral modifications. People often use these drugs in conjunction with dieting, markedly reducing caloric intake. However, calories provide the fuel your body needs to function. A person’s body can’t keep up with normal activity during rapid and extreme diet and weight loss, and muscles atrophy because of this reduced activity. With less energy for anabolic processes to maintain muscle, the balance shifts further to catabolism.

- Your appetite is suppressed. Patients taking GLP-1s crave carbohydrates and fat instead of protein, leading to muscle loss.

How to Optimize Anabolism and Catabolism to Lose Weight Safely

Prioritize losing the right weight: fat, not muscle mass. At Banner Peak Health, we don’t think about weight in isolation. Instead, we consider the relationship between anabolism and catabolism, and we use several techniques to facilitate fat loss and preserve muscle.

If you’re on a GLP-1 receptor agonist, you’ll complete an InBody composition scan every time you visit the office. We’ll measure your muscle mass vs. fat mass to ensure you lose less of the former and more of the latter.

We also help our patients increase their protein intake as a percentage of reduced total calories.

Healthy weight loss requires work — aerobic exercise, strength training, and protein consumption — and our physicians are here to help. Reach out today and tell us about your weight loss goals.

Beyond the Pill: Natural Ways to Fight Depression

Unfortunately, depression isn’t rare. Approximately 3.8% of people experience depression at any point during the year (including 5% of adults), and every individual has a 29% risk of being diagnosed with depression in their lifetime.

Although medication is a common treatment for depression, it’s not a cure-all. The response rate of a major symptom reduction is usually only 50–60%. (A placebo’s symptom reduction rate is 30–40%.)

Introduced in the 1980s, Prozac was the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). However, the difference between the drug effect and the placebo was slight, and so few studies showed efficacy that Pfizer had to cherry-pick studies to get FDA approval.

Drugs don’t cure depression. We still don’t understand the biochemistry behind depression, which is why our drugs’ efficacy is so poor.

Therapy has documented efficacy for depression. It’s harder to study than drugs, but medication and therapy combined can achieve up to an 80% reduction in symptom scores.

Because we don’t have a single depression-busting magic bullet, we treat it through stacking (also called the “everything but the kitchen sink” method). By bundling modalities, including natural ways to fight depression, we see more benefits than with any single treatment.

So, can depression be treated without medication? Absolutely.

A Physician’s Caveat

Medical literature offers varying degrees of support for natural ways to fight depression.

The safer a treatment, the more likely I am to recommend it to a patient even if it lacks strong, supportive data. It all comes down to the risk-benefit ratio — if a treatment’s risk is low enough, I’ll try it.

These therapies are safe, and I’m not bothered by the paucity of data on their efficacy. That said, don’t consider or use them in lieu of medication or therapies prescribed by your physician. Talk to your doctor first.

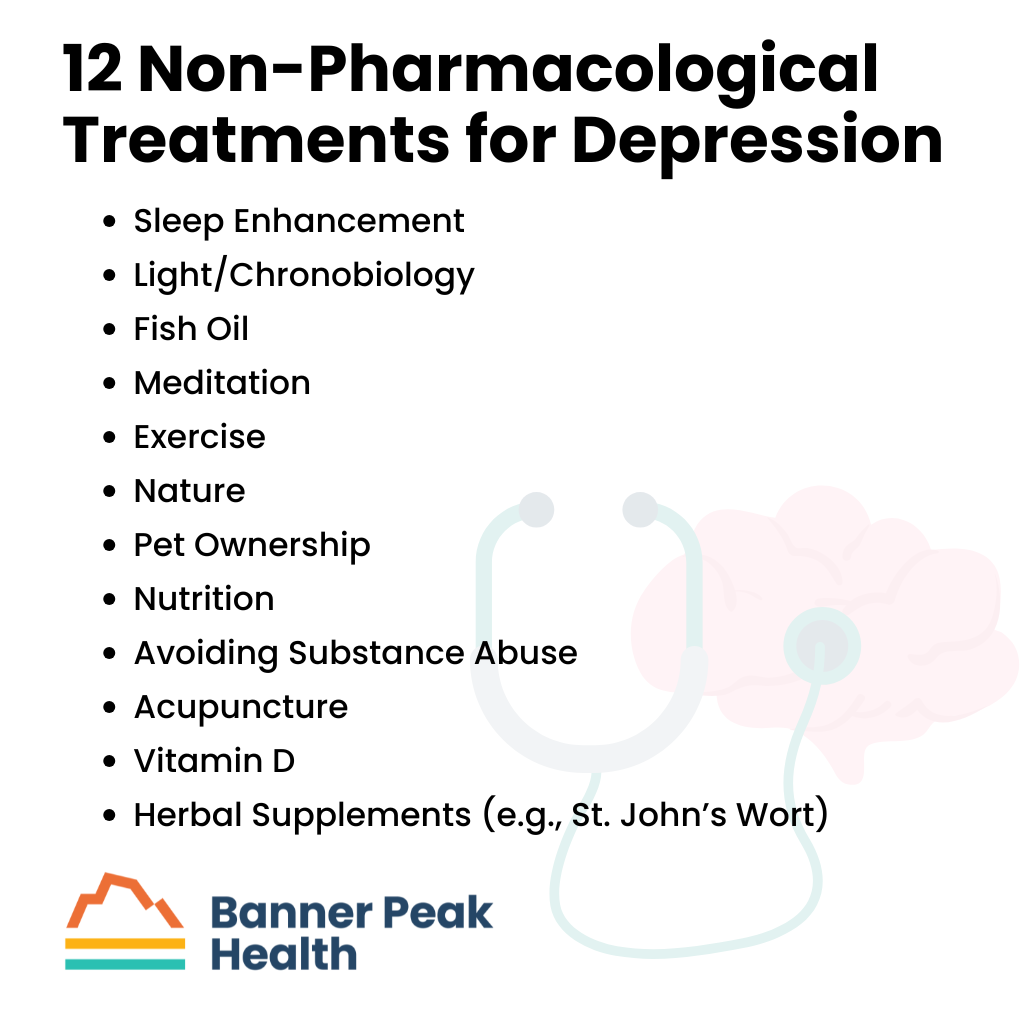

12 Non-Pharmacological Treatments for Depression

The following are my top recommendations on natural ways to fight depression and other non-pharmacological treatments for depression:

Sleep Enhancement

Sleep impairment is associated with emotional illness, including bipolar disorder and depression. Any action taken to enhance sleep mitigates these conditions’ symptom burden.

Every other treatment on this list improves sleep.

Light/Chronobiology

Circadian rhythm is a large component of emotional illnesses such as bipolar disorder and depression. Re-synchronizing your circadian rhythm with light therapy can play a prominent role in these therapies.

At Banner Peak Health, we recommend the TUO light bulb to help re-sync your circadian rhythm. Get as much morning light as possible, and be cautious of using sunglasses during the first few hours of the day. Morning light is a powerful signal for your circadian rhythm.

Fish Oil

While literature supporting its effects on the heart is controversial, literature supporting fish oil’s antidepressant effects is strong. Just one to two grams daily helps manage depression (and may also improve your heart health).

Meditation

Mental health is associated with greater sympathetic discharge (cortisol, stress, and anxiety). Meditation, including breathing exercises, reduces your stress response and improves your mental health.

Exercise

Aerobic and strength training exercises reduce stress, enhance sleep, and improve mood. It’s a valuable weapon in the fight against depression.

Nature

We’ve evolved over hundreds of thousands of years to exist in nature. Our urban environment is so new that we haven’t evolutionarily adapted to it yet. Exposing yourself to nature helps you harness your evolution to your benefit.

Pet Ownership

People who own pets or even have access to visiting pets in nursing facilities have better mental health.

We live more solitary lives than ever before in our evolutionary history. Any contact with human beings or pets connects us to how we evolved to survive, both physically and mentally.

Nutrition

When our mental health declines, we crave substances like sugar, fats, and caffeine that worsen, rather than improve, our emotional state.

To improve your mental health, adopt a healthier diet.

Avoiding Substance Abuse

When we’re not feeling our best, we gravitate toward substances that hurt our mental health. We’re better off when we eliminate marijuana, alcohol, nicotine, and other counterproductive exogenous substances from our lives.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a proven non-pharmacological treatment for depression. Anyone who’s had it has felt its calming, centering effects. It’s worth a try if it’s available in your area.

Vitamin D

Higher vitamin D levels are associated with many better medical outcomes, including mental health. However, whether taking supplemental vitamin D improves medical outcomes remains controversial. Fortunately, taking supplemental vitamin D is safe in almost all circumstances.

Of note, please discuss this with your doctor, as there are some rare conditions in which over-the-counter vitamin D may not be helpful.

Herbal Supplements (e.g., St. John’s Wort)

St. John’s Wort is one of many substances and herbal supplements recommended for treating depression. However, the data documenting their efficacy is meager, and the side-effect ratio for some supplements is not as benign as other modalities we’ve discussed.

For example, St. John’s Wort can cause the following side effects:

- Headaches

- Dry mouth

- Confusion

- Anxiety

- Stomach upset

- Drug interactions

I’m including St. John’s Wort and other herbal supplements for completeness, but the risk-benefit ratio is not as good as the other modalities on this list. People inevitably ask about them, but I’m not bullish on them.

Today’s Takeaways

Stress and depression are ever-present in our modern world. Fortunately, there are many effective non-pharmacological treatments for depression with exceptional risk-benefit ratios.

If you’re struggling with your mental health, please reach out to a therapist or schedule an appointment with a Banner Peak Health physician. We’re here to help.

If you need immediate assistance or know someone who does, help is available 24/7 at the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. To access it, dial 988 from any phone.

How to Keep Your Knees Healthy: Preventing Injuries and Pain

With enough wear and tear, all mechanical devices (e.g., engines, hinges, tires, etc.) degrade.

For many years, conventional wisdom said the same about our knees. They were just biological hinges that would inevitably give out over time, especially with overuse, such as running. Trying to figure out how to keep your knees healthy was a lost cause, especially for athletes.

A study that began in 1984 turned this notion on its head.

How to Keep Your Knees Healthy: The Shocking Truth

Doctors at Stanford tracked two study groups to test the hypothesis that knees are analogous to mechanical hinges that wear out over time.

The study followed 45 recreational, long-distance runners and 53 non-runner controls over 18 years. The participants were predominantly men with a mean age of 58. The runners had at least 10 years of running experience and ran an average of five hours per week.

At the beginning of the study, 6.7% of the runners and 0% of the non-runners showed X-ray evidence of arthritis. The participants had X-rays of their knees taken every few years.

At the end of the 18-year study, the results flabbergasted everyone: 20% of the runners had evidence of some form of arthritis, while 32% of the controls did. Even more startling? Only 2.2% of the runners had severe, disabling arthritis, while 9.4% of the controls did.

The non-running controls had over four times the rate of severe arthritis in their knees as the runners. The results contradicted the original hypothesis and debunked the myth that running damages knees.

Important Caveats

The study’s participants were:

- Uninjured

- Mostly men

- Over age 50

- Recreational, long-distance runners

The study definitively answered whether knees wear out over time for that population. They don’t.

Unpacking the Conventional Wisdom

Where did the notion that athletes have “bad” knees (or are destined to) come from?

Countervailing literature on high-intensity sports, including ballet, soccer, wrestling, and weightlifting, shows that athletes can have three to six times the level of degenerative arthritis as non-athletes.

When you examine the literature for sports that have increased rates of degenerative arthritis and remove injured athletes, there’s no increased risk of degenerative arthritis. The literature tells us that running makes a healthy, uninjured knee healthier.

Conversely, a sport that injures a knee causes the knee to wear out faster. The goal is to safely participate in sports that can strengthen the knee without injuring it. How can you find the right balance?

Let’s examine the knee’s anatomy to understand why this happens and how to keep your knees healthy with appropriate exercise.

The Knee’s Anatomy

The knee contains “hard stuff” and “less hard stuff.”

The “hard stuff” is bones:

- Femur

- Patella

- Tibia

- Fibula

The “less hard stuff” is cartilaginous tissue, tendons, and ligaments:

- Lateral meniscus

- Medial meniscus

- Lateral collateral ligament

- Medial collateral ligament

- Anterior cruciate ligament

The lateral and medial meniscus act like washers to cushion the areas between the bones. The ligaments connect the bones and align your knee.

When the anatomy works well, exercise perfuses the soft tissues and cartilage. Cartilage is avascular, meaning it contains few or no blood vessels. The medial meniscus, for example, gets nutrition from the synovial fluid.

Synovial fluid bathes and lubricates the entire knee joint when you move your knee. The more effectively you move your knee, the more you nourish those soft tissues.

If you injure your knee — for instance, if you tear a meniscus or ligament — you change the knee’s mechanical alignment. At that point, you’ve disturbed the anatomy of the knee and changed how the force is distributed within the joint, which increases your likelihood of generative arthritis and joint wear.

In contrast, maintaining an injury-free knee strengthens it.

How to Keep Your Knees Healthy

With this understanding of anatomy and pathophysiology, here’s how to keep your knees healthy:

- Exercise. It strengthens the bones and enhances the knee’s surrounding musculature, protecting and aligning it. Exercise also moves the synovial fluid around, maintaining cartilage health.

- Practice extreme caution with high-impact, injury-prone sports. Every sport, even running, can injure you. If you participate in high-risk sports, maintain your flexibility and strength, and don’t overdo it.

- Remember that running is a double-edged sword. When done properly, it’s good for your knees, but if you injure your knees while running, your risk of arthritis increases. Practice safe running techniques:

- Pay attention to your gait. Watch videos online or talk to a coach.

- Wear appropriate footwear. Use insoles if you need them for proper alignment.

- Avoid carrying extra body weight if possible, but if you must, maintain strength and flexibility. Extra weight demands more of your knees.

If you feel pain, remember that musculoskeletal pain is a message from your body. Don’t ignore it. Figure out what your body is trying to tell you.

Knee pain can be a valuable lesson if you listen to your body and decipher its message. Did you run too far? Do you have a bad gait? Do you need different shoes? Listening to your body is the best way to keep your knees healthy.

At Banner Peak Health, we’re proud to offer the resources you need to achieve optimal health through our Outperform program, including access to fitness instructors. Contact us today to take advantage.

Your Guide to Belly Breathing: Benefits, Techniques, and More

I’m 62 years old and have taken about 500 million breaths. Recently, I learned that most of these breaths were done improperly.

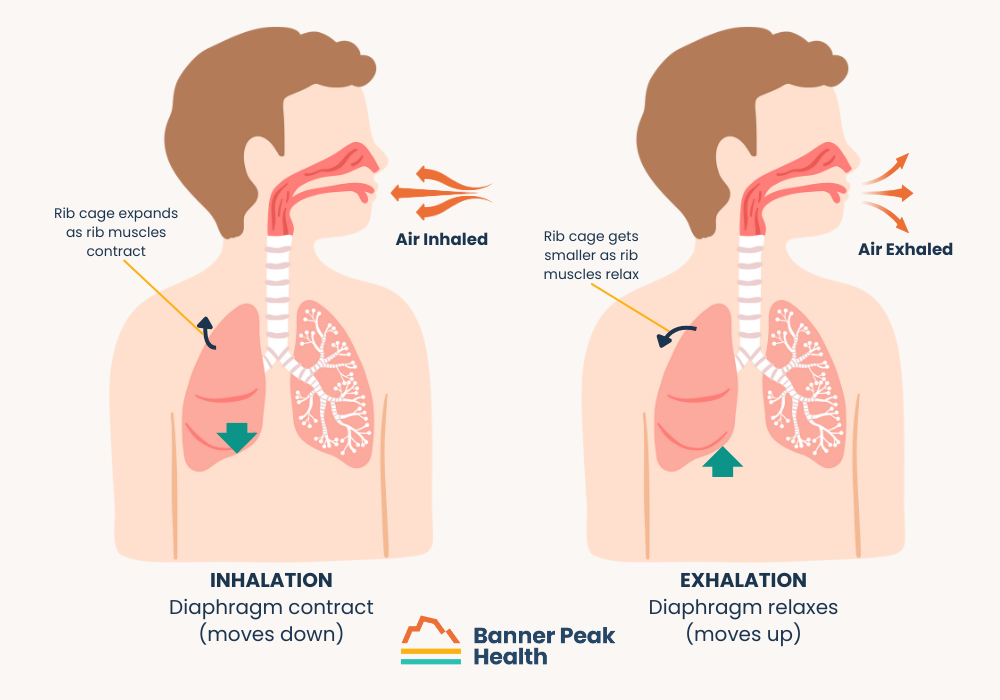

Why do we breathe? We take in oxygen for our metabolism to generate energy. We exhale CO2 (metabolism’s byproduct) to expel it from our bodies.

Given the vital necessity of breathing, we’ve evolved a complicated, sometimes redundant breathing mechanism. It involves a multitude of muscles that expand the lungs (to inhale) and natural elasticity that contracts them (to exhale). The muscles involved are:

- In the neck

- In the shoulder girdle

- In the chest wall

- The diaphragm (one big muscle that lines the bottom of our lungs and depresses)

These muscles make up the redundant anatomy, which we use in different combinations.

Different Forms of Breathing

There are two types of breathing: chest breathing and belly breathing.

Chest breathing is the predominant type and involves the muscles on the sides of the rib cage, in the neck, and in the shoulder girdle.

Belly breathing, or diaphragmatic breathing, relies on the diaphragm to depress the lungs into the abdominal cavity and enlarge them.

How Breathing Develops

How Breathing Develops

As newborns and young children, we default to belly or diaphragmatic breathing. It’s more efficient — bringing the diaphragm down expands the lungs more efficiently than chest breathing.

Because of the functioning of our nervous systems, most of us transition to chest breathing at some point in life. As we become more anxious, we become more sympathetically driven (i.e., the sympathetic nervous system, fight or flight) in how our autonomic nervous systems coordinate our breathing. We tend to take more shallow, rapid breaths with our chest walls.

Belly breathing is more calming. It involves a more parasympathetic (i.e., rest and digest) tone that consists of the diaphragm coming downward.

The Cycle of Stressful Breathing

Improper breathing creates a vicious cycle: We breathe improperly because we’re stressed, and our breathing mechanism becomes more stressed (sympathetically driven) because we breathe improperly.

So, how can we escape the cycle?

We can retrain our bodies to use distinctively diaphragmatic breathing like babies do. Watching a baby breathe, you’ll see the tummy move up and down. That’s the kind of breathing you want to mimic.

Retraining Your Brain to Breathe Right

The autonomic nervous system is a two-way street. It causes us to breathe a certain way; however, if we consciously breathe a certain way, we can rebalance our autonomic nervous system.

This rebalancing begins with consciously recapturing (or relearning) diaphragmatic breathing.

Benefits of Diaphragmatic (Belly) Breathing

Studies show many benefits associated with belly breathing. The most common are:

- Increased parasympathetic tone, which can lead to:

- Increased heart rate variability

- Reduced anxiety

- Reduced cortisol

- Reduced blood pressure

- Reduced heart rate

- More effective and efficient breathing:

- More oxygen is taken in

- More CO2 is expelled

- Increased athletic performance

- Improved cognition

- Reduction in GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease)

- Reduced neck stress

- Improved posture

Organs below the diaphragm and muscles above it work better with belly breathing. People who belly breathe experience less stress in their neck and shoulder muscles and also have less gastroesophageal reflux.

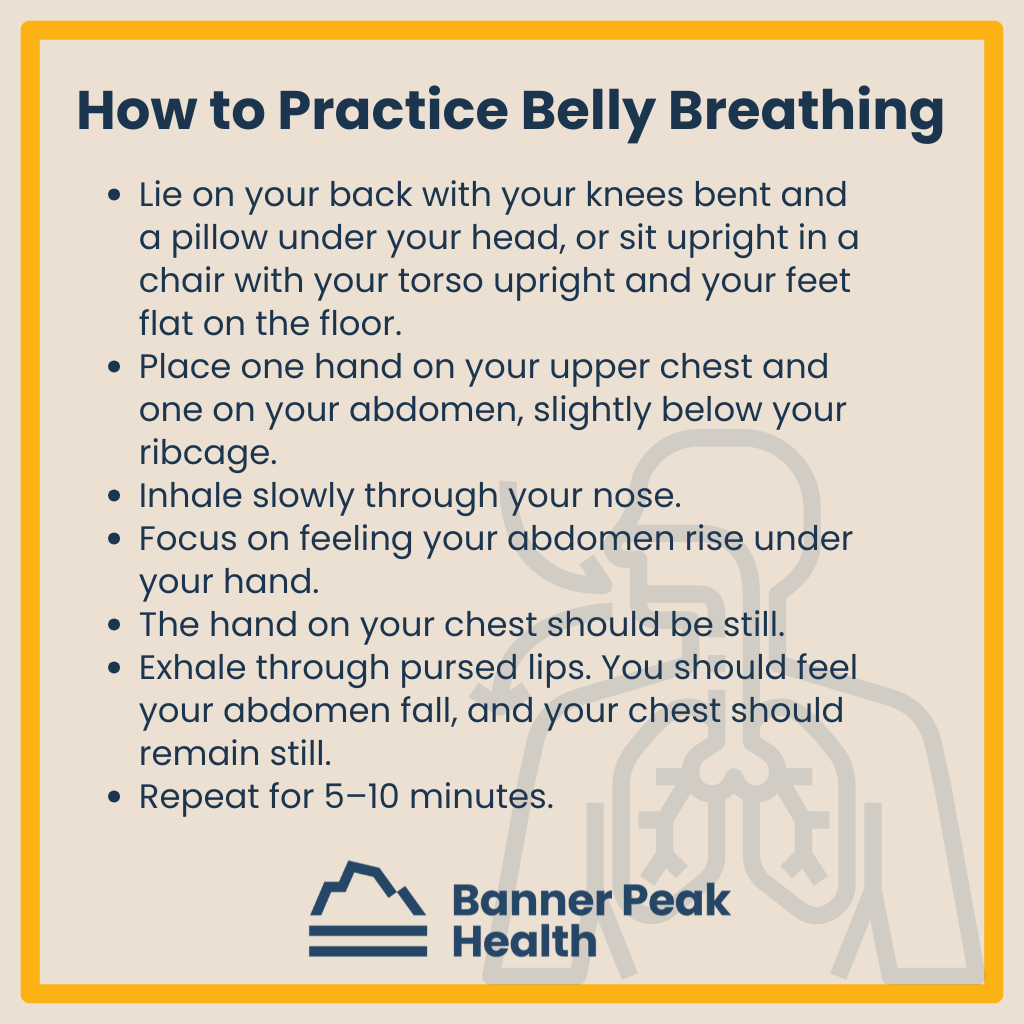

How to Practice Belly Breathing

Although breathing is an unconscious process, we can reprogram our default (how our unconscious breathing works) through conscious training.

To apply this training, follow these instructions for five to 10 minutes, three to four times daily:

- Lie on your back with your knees bent and a pillow under your head, or sit upright in a chair with your torso upright and your feet flat on the floor.

- Place one hand on your upper chest and one on your abdomen, slightly below your ribcage.

- Inhale slowly through your nose.

- Focus on feeling your abdomen rise under your hand.

- The hand on your chest should be still.

- Exhale through pursed lips. You should feel your abdomen fall, and your chest should remain still.

- Repeat for 5–10 minutes.

Let your hands guide you. If the hand on your chest moves, you’ve got it wrong. Correct your inhalation so only the hand on your abdomen moves.

You’ll have to think about every single breath. Eventually, this technique will lead to a shift in your automatic breathing.

As-Needed Breathing Techniques

We all deal with stressful situations in which focused breathing can help us relax. These techniques will help you do just that, and plenty of literature supports their efficacy.

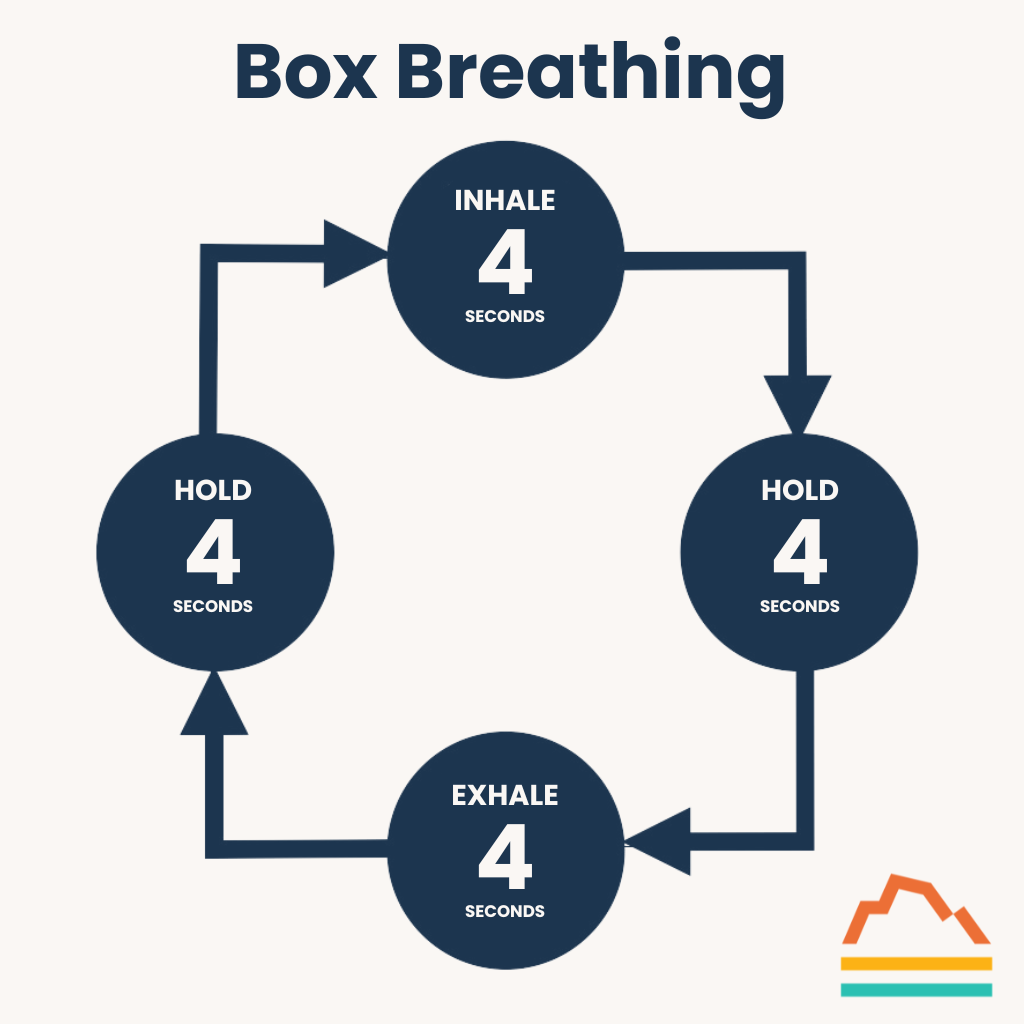

Box Breathing

Box breathing is perfect for improving focus and marshaling your resources when you’re feeling overwhelmed. Don’t think of it as just another hippy-dippy, granola-loving new-age practice. Navy SEALs and tactical police officers use it in high-stress situations.

Here’s how to start:

- Inhale for a count of four.

- Hold your breath for a count of four.

- Exhale for a count of four.

- Hold your breath for a count of four.

- Repeat.

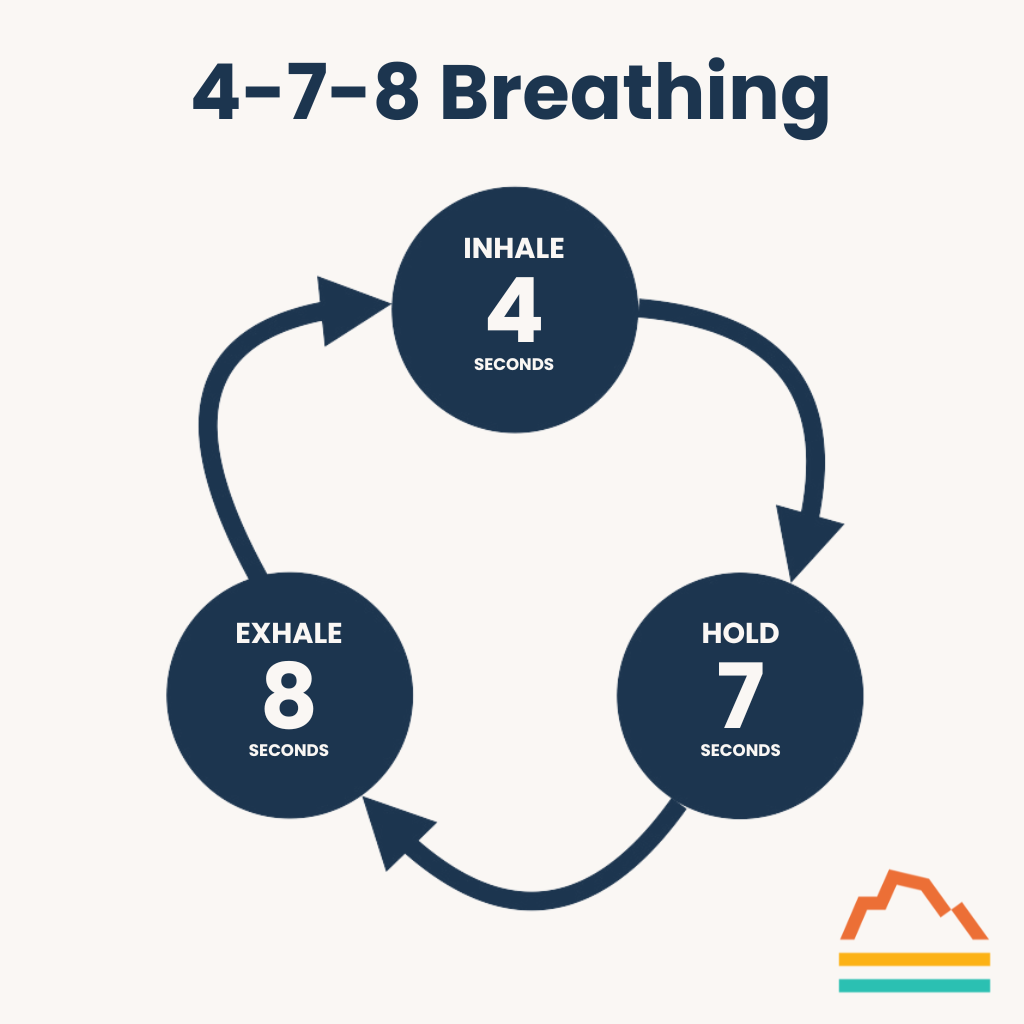

4-7-8 Breathing

When you’re feeling anxious or stressed, the 4-7-8 breathing technique can help. Many people also find it useful when they have trouble falling asleep.

Here’s how to practice it:

- Inhale through your nose into your belly (use belly breathing) for four seconds.

- Hold your breath for seven seconds.

- Exhale slowly through pursed lips for eight seconds.

- Repeat.

Today’s Takeaways

After so many blogs chronicling stress’s adverse effects, I’m happy to offer practical, cheap, operational techniques to tip the scales in the other direction.

Try paying attention to how you breathe. See if making a conscious effort to revert back to belly breathing improves your life.

Identifying the latest science-backed ways to improve your health is a huge part of what we do at Banner Peak Health. If you want to learn how we can help you improve yours, we’re just a phone call or email away.

How to Lower Diastolic Blood Pressure

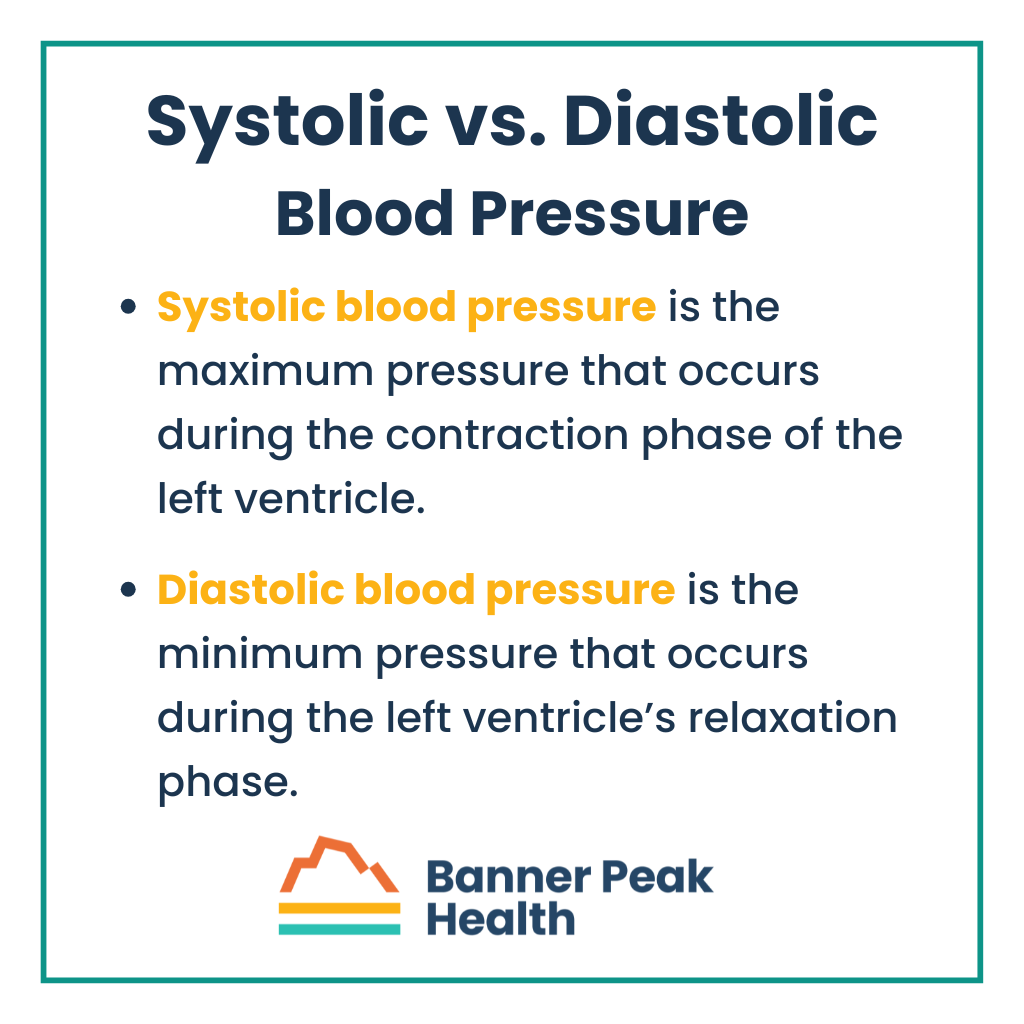

You might be curious about your blood pressure. However, it’s not a single measurement because the doctor gives you two numbers. What do those numbers mean?

The top (larger) number is your systolic blood pressure, while the bottom (smaller) number is your diastolic blood pressure.

Do you know how to lower diastolic blood pressure if it’s too high?

Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

Systolic blood pressure is the maximum pressure that occurs during the contraction phase of the left ventricle, the portion of the heart that pumps blood through the arteries of the body.

Diastolic blood pressure is the minimum pressure that occurs during the left ventricle’s relaxation phase.

Your blood pressure varies according to physiological changes, and readings can change due to sampling and measurement errors. Obtaining an accurate blood pressure reading can be challenging, and normal blood pressure isn’t as straightforward as it seems.

However, knowing your overall blood pressure and whether it tends to run high is important since this indicates many health risks.

High Blood Pressure Causes

Systolic pressure is primarily influenced by the stiffening of the larger arteries. As we age, our arteries have more exposure to illnesses such as high blood pressure, diabetes, and elevated cholesterol that can thicken the artery walls and reduce compliance. (And, yes, high blood pressure can cause further high blood pressure, which is why timely diagnosis and treatment are vital.)

Imagine trying to blow up a balloon. It won’t take as much pressure to blow up a soft, new balloon as it would to blow up a stiff, old balloon.

Your diastolic pressure is measured during relaxation (between heartbeats). The anatomy of the resistance is thought to be slightly different. Diastolic relates to the stiffening of smaller vessels rather than larger vessels. This process can be influenced by stress, alcohol, extra body weight, as well as excess hormone levels of thyroid, cortisol, aldosterone, norepinephrine, and epinephrine.

Whereas systolic and mixed high blood pressure become more common with age, isolated diastolic occurs more often in people under 50 years old.

How to Lower Diastolic Blood Pressure

We consider “high blood pressure” as systolic greater than 130 and diastolic greater than 80.

Often, both systolic and diastolic measurements are elevated. Frequently, only the systolic measurement is elevated, particularly in the elderly. The majority of the time in these cases we cannot identify a particular cause of the elevated blood pressure and treat with medication to lower the blood pressure.

It’s much rarer for someone to have normal systolic but elevated diastolic blood pressure. Isolated diastolic hypertension affects an estimated 6.5% of the U.S. population. However, these cases are more often associated with disease states such as hormonal imbalances that need to be identified and treated rather than just using a medication to lower the blood pressure.

With a doctor’s help, you can lower high diastolic blood pressure by identifying an underlying condition in addition to lifestyle changes and medication.

Today’s Takeaways

Approximately 48.1% of adults in the U.S. have high blood pressure. While extremely common, elevated blood pressure can be dangerous and worsen if left untreated. Please take it seriously.

In the relatively rare event you have isolated diastolic hypertension — a different form of blood pressure — you will need more investigation by your physician to detect and treat an underlying cause, rather than merely taking high blood pressure medication.

But if you’ve been wondering how to lower diastolic blood pressure because yours is too high, it’s time to talk to your doctor.

What Is Non-HDL Cholesterol? Understanding Your Heart Health

When doctors order traditional lipid panels as part of annual blood tests, patients see “non-HDL” and often ask, “What is non-HDL cholesterol?”

The question reminds me of reading Shakespeare’s “King Henry IV” in high school.

In the play, the character Prince Hal has five different names. This confused me until I realized all those names refer to the same person. Once I understood that, the play and plot became clearer.

The terminology used in medicine influences our comprehension and treatment options. Non-HDL is one of the least understood characters in the cholesterol metabolism “play.”

Blood Is Like “Oil and Water”

Our blood isn’t a homogenous liquid. It’s more like an oil and vinegar salad dressing. In this example, the water component of our blood is the “vinegar,” and the fat is analogous to the oil.

Fat doesn’t dissolve in water. Therefore, the fat forms little protein- and phospholipid-covered balls suspended in the blood.

Cholesterol’s Purpose and “Cast of Characters”

There’s no such thing as “good” cholesterol or “bad” cholesterol. A cholesterol molecule is exactly the same whether it’s contained in a “good” HDL particle or a “bad” LDL particle. We need cholesterol to build cell walls, manufacture hormones such as testosterone, and make bile acids to digest our food. Too much cholesterol in the wrong place, such as the walls of our arteries, confers its “badness.”

Understanding the “characters” that comprise the “play” of cholesterol metabolism is helpful.

“Main Characters”

HDL and LDL are the “main characters” featured in cholesterol. You’ll see them on your lipid panels.

- LDL (low-density lipoprotein):

- It carries cholesterol from the liver to cells and the rest of the body.

- It can carry excess cholesterol to arterial walls to create dangerous buildup.

- HDL (high-density lipoprotein):

- It carries cholesterol from the body back to the liver for reprocessing.

- It reduces the amount of cholesterol deposited on arterial walls, where it can cause damage.

“Supporting Characters”

The following are some “supporting characters” to help you better understand cholesterol.

- VLDL (very low-density lipoprotein):

- It primarily contains triglycerides and very small amounts of cholesterol.

- VLDL transports triglycerides from the liver out to the body.

- Your body uses these triglycerides for immediate energy in muscles or energy storage in fat cells.

- IDL (intermediate density lipoprotein):

- As a VLDL particle delivers its triglycerides, it becomes proportionally richer in cholesterol and becomes an IDL particle.

- Chylomicron (ultra-low-density lipoprotein):

- It’s primarily a triglyceride-containing particle that transports fat from the gut to the blood.

What Is Non-HDL Cholesterol?

Non-HDL cholesterol is your total cholesterol minus HDL cholesterol. In other words, non-HDL cholesterol is the sum of LDL, VLDL, IDL, and chylomicron.

Why Measure Non-HDL?

Non-HDL cholesterol is easy, cheap, and convenient to measure. It’s a better predictor of coronary artery disease risk than LDL alone — especially when LDL isn’t elevated.

The Crucial Role of Lipoprotein B-100

Returning to the oil and water analogy, you might imagine a chaotic mix of tiny balls floating through your bloodstream. However, that’s not the case.

Each ball has a set of lipoprotein markers that identify its contents and the route it must take through the body to arrive at its designated location. Think of it like a passport.

A single lipoprotein called B-100 (“APOB”) occurs on each non-HDL particle.

Why is it important?

All non-HDL particles confer risk because they contain cholesterol, and blood vessel walls can absorb them. This means non-HDL cholesterol is potentially atherosclerotic and can contribute to cardiac disease.

Today’s Takeaways

Gaining a better understanding of lipid physiology and your lipid panel is beneficial for reading lab results and becoming more informed. This way, you won’t need to ask, “What is non-HDL cholesterol?”

Banner Peak Health employs non-HDL (or APOB) because it’s the most accurate risk assessment tool. The more accurately we can gain insight into your atherosclerotic risk, the more accurately we can target and mitigate that risk. Maintaining and improving your health is always our priority.