We’re officially in the throes of an “infodemic.” Every day, we’re inundated with more information than we can process about a variety of topics, especially medicine.

Why is this happening? One reason is that there exists a bias in medical literature reporting. Every individual and institution in the research process has the potential to overinflate their findings’ value, seeking to gain greater exposure from the press.

Researchers are also pressured to produce noteworthy results. Impressive studies endow prestige and enhance scientists’ and journalists’ careers. Because there’s so much at stake, there’s a tendency to mislead with less-than-accurate information.

Combine that with the press’s tendency to report overly optimistic or frightening statistics. Their goal is to get readers to click, read, and subscribe.

I want to give you the skills to navigate this infodemic of medical literature. Once you finish this post, you’ll be able to read critically and discern between relevant data and sensationalism.

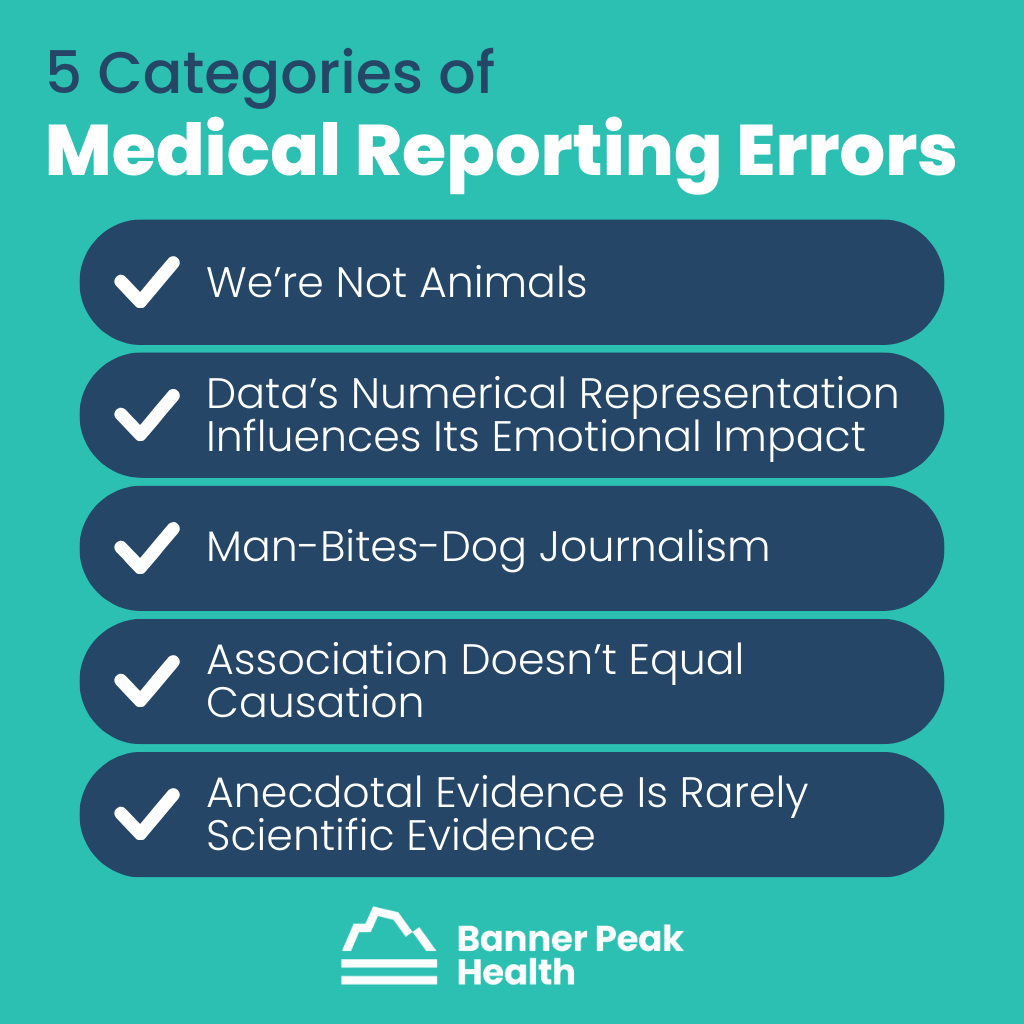

5 Categories of Errors

I’ve identified five categories of common medical reporting errors.

1. We’re Not Animals

We have neither fur nor tails, yet many studies found in medical literature involve animals.

Animal experimentation is part of our research method. Only a minute percentage of discoveries from animal models ever impact human healthcare. Regardless, these studies often excite the press.

Example: Taurine is an amino acid shown to improve health and extend lifespan in mice. However, because of inherent physiological differences, there’s almost no chance this will ever be relevant to humans.

2. Data’s Numerical Representation Influences Its Emotional Impact

Data often tells more than one story, and journalists are storytellers. That can be a dangerous combination.

When the press presents the same data in multiple ways, people can interpret it differently, and the information can have various emotional effects. It can even influence public policy.

Example: The Women’s Health Initiative, which began in 1991, explored hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in postmenopausal women.

One randomized part of the study examined 16,000 women. In a subset study, 678 women — 385 from the HRT group and 293 from the placebo group — received a breast cancer diagnosis.

In 2005, the press reported those results as a 23.5% increased risk of breast cancer from HRT, a frightening finding. This statistic is true, breast cancer did occur at a rate of 0.42% per year in the drug group and 0.34% in the placebo group.

However, the results are more nuanced than that. Each year, for every 1,000 women in the trial, an average of 4.2 women on HRT could expect a breast cancer diagnosis, while an average of 3.4 women on the placebo could expect the same. There was a difference of only one woman per 1,000 each year between the two groups.

The press chose to express the data in a sensational way to entice readers to click on headlines and purchase newspapers. That single statistic changed women’s healthcare for over 20 years. Doctors and patients have been fearful of estrogen replacement therapy. As a result, an entire generation of postmenopausal women have been fearful of using a relatively safe treatment.

3. Man-Bites-Dog Journalism

Science is rarely about the result of any single study but the preponderance of evidence based on the compilation of many studies. However, when a touted study contrasts prevailing wisdom, it’s more likely to appear in the press. Journalists’ prerogative is to grab attention, and contrarian headlines accomplish that.

Example: In 2017, the Independent ran an article quoting one doctor who said, “Sugar benefits your brain health.”

This article expressed the opinions of a single doctor, who states that sugar may not be as harmful as we think it is.

It only became popular because it’s an assertion that goes against prevailing wisdom. In science and medicine, beware the contrarian.

4. Association Doesn’t Equal Causation

Human beings are not lab animals, particularly regarding our diet. It’s impossible to run randomized control trials on humans because we can’t control and measure everything test subjects eat against a control group.

Therefore, we rely on epidemiologic studies, which examine differences in people’s eating habits and try to correlate them with different health outcomes. Unfortunately, this form of study is notoriously susceptible to identifying associations that aren’t necessarily causal.

Example: For many years, red wine was believed to confer a health advantage. The consumption of red wine is associated with many other healthful behaviors, such as eating fresh fruits, vegetables, and healthier oils. Therefore, red wine is a confounder — associated with better health, but not causal.

Nutrition literature is particularly prone to miraculous attributions to certain foods.

5. Anecdotal Evidence Is Rarely Scientific Evidence

Anecdotal evidence may be exciting and compelling, but it’s rarely enough to inform or change the practice of medicine.

Example: The media is full of anecdotal evidence from people who successfully combatted their COVID-19 symptoms using ivermectin or azithromycin, both of which have been proven ineffective in randomized control trials.

Today’s Takeaways

Before you become too excited or too frightened by a medical article, remember the following:

- Humans are not animals.

- Be leery of data expressed as percent change rather than an absolute number.

- Beware the contrarian. Don’t take it at face value if something goes against all conventional thinking.

- Association does not equal causation.

- Sample size matters. Don’t extrapolate universal truths from single or small sets of unique events.

There are always exceptions to these rules. Every day, the media reports valid science, and every day, they sensationalize. By being an informed, discriminating reader, you’re better equipped to find the kernels of truth and stay above the fluff.

Barry Rotman, MD

For over 30 years in medicine, Dr. Rotman has dedicated himself to excellence. With patients’ health as his top priority, he opened his own concierge medical practice in 2007 to practice medicine in a way that lets him truly serve their best interests.